The Making of a Cookbook

About Abe, Adrienne and Fat Rice

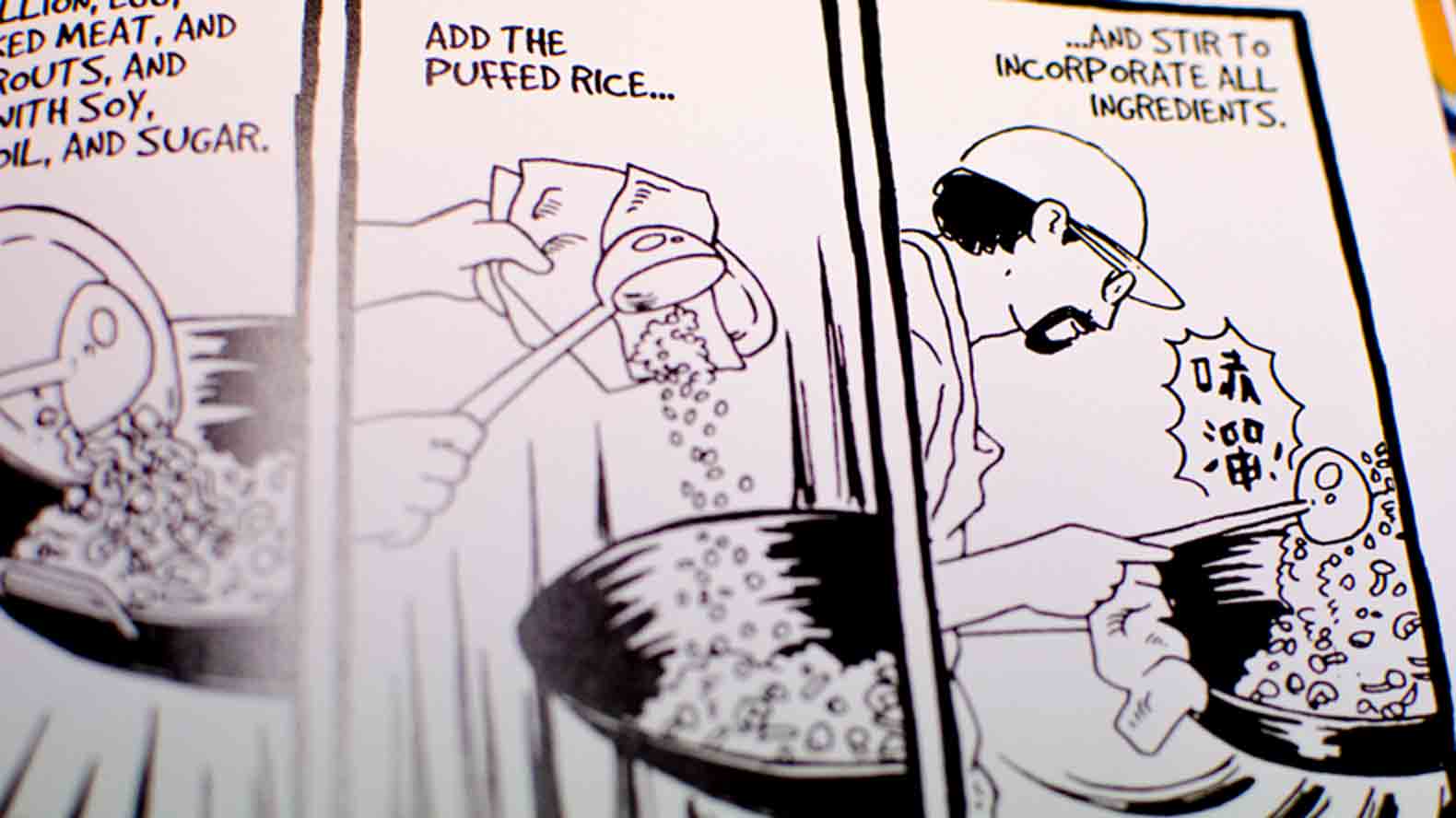

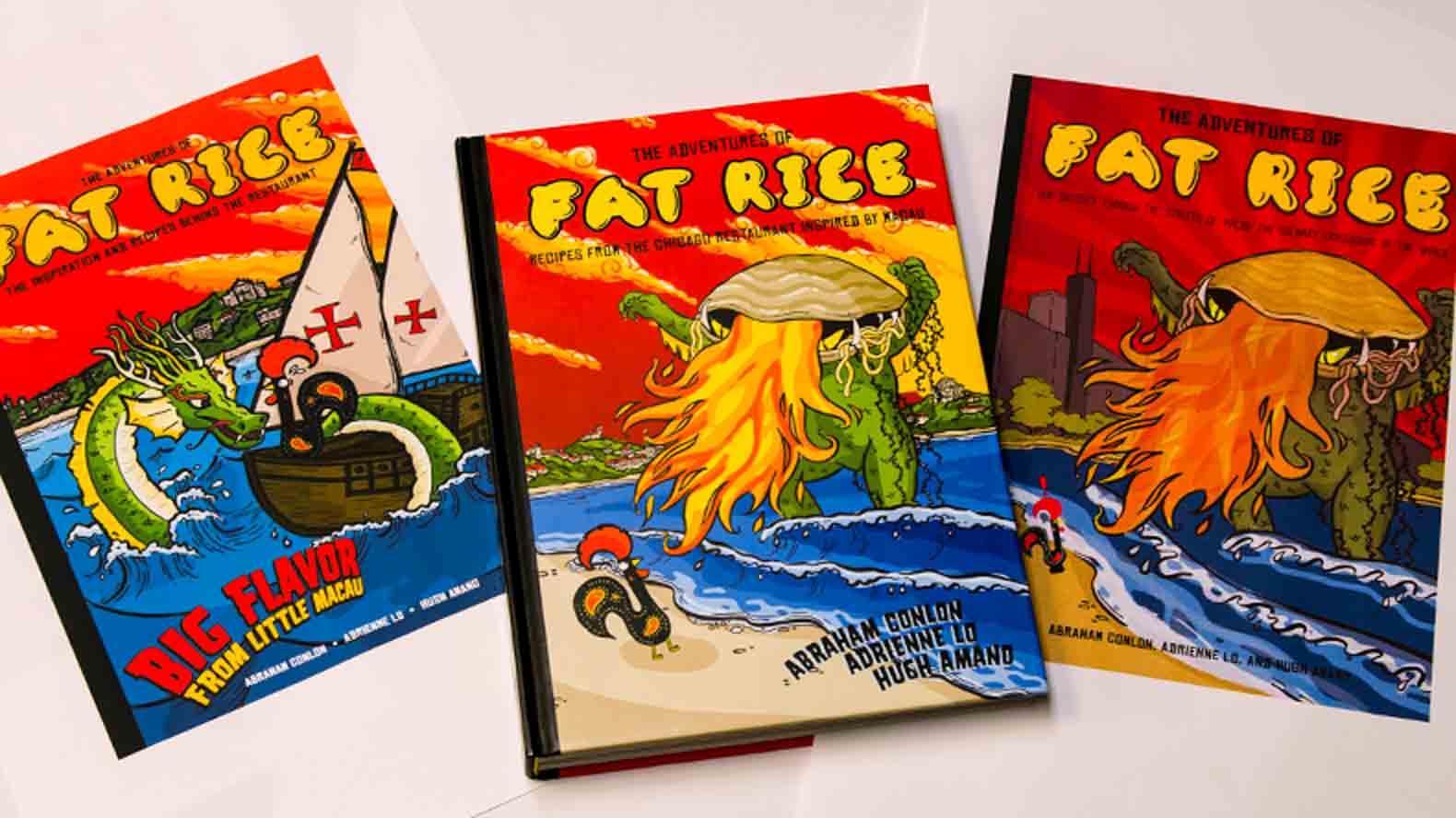

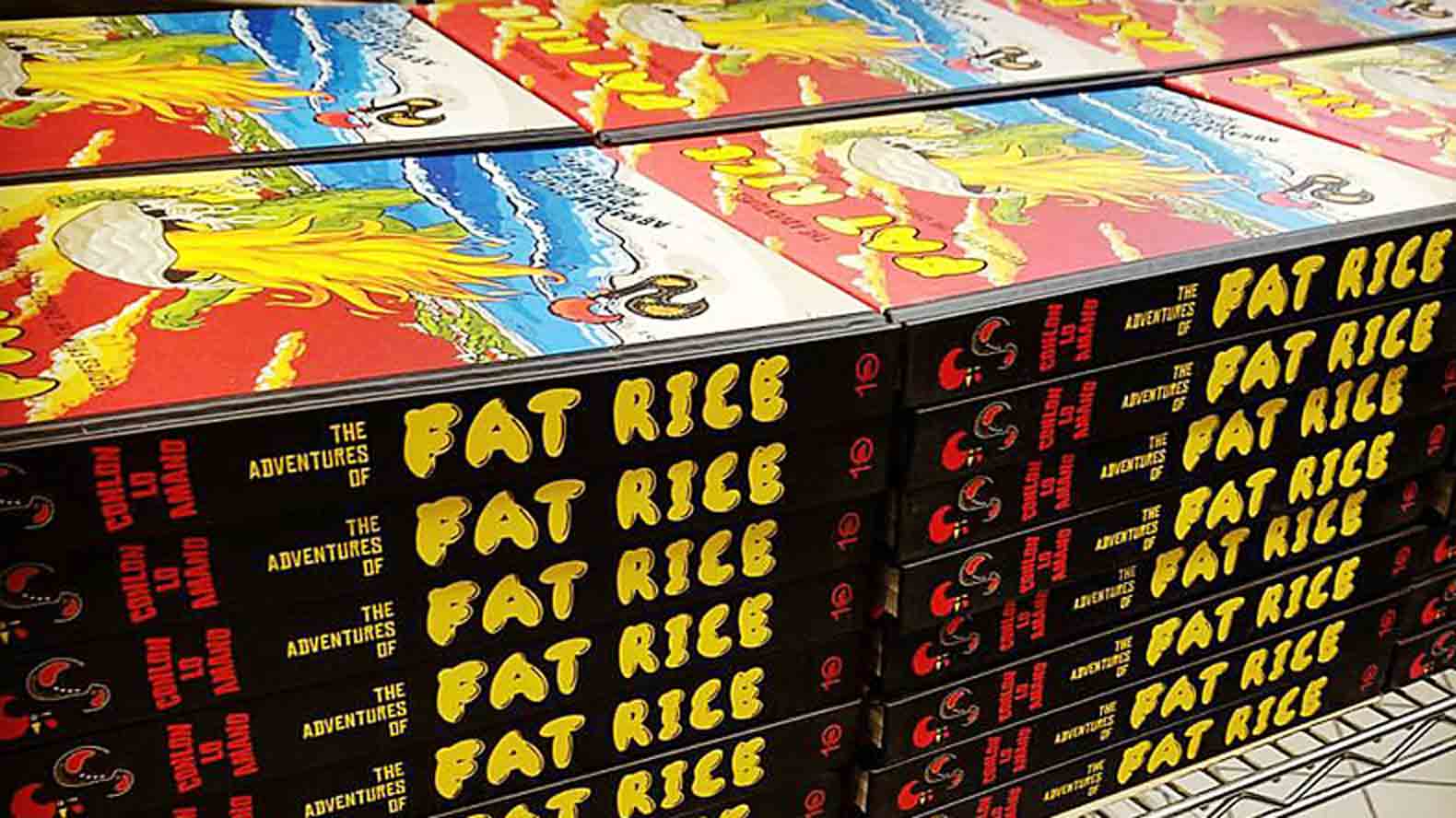

The cover of The Adventures of Fat Rice is not a food porn-y image of a dish that has been styled within an inch of its life. It’s a drawing of a giant fire-breathing chilli clam emerging from the sea to attack the city of Macau, on whose beachfront sits a small rooster (aka the galo)—looking as alarmed as anyone would at the prospect of death-by-chilli-clam. It’s a comic book cover that vibes a lot more skater than serious chef-historian, and that’s not by accident: Conlon and Lo don’t take themselves too seriously. They are serious chefs, and utterly passionate about their food and Macau and Macanese food, but would rather die than be pretentious about it. That image might be what best represents the book, the people and restaurant behind it.

Conlon is tall and thin; wiry in frame and wired in personality. If he were a comic book character, he would have those wavy lines that signify frenetic energy coming off of him. I tried to count the number of times people I interviewed for this article referred to him as “intense,” but lost track. Suffice it to say, it came up a lot. In contrast (and one suspects, by necessity), Adrienne Lo is calm, even serene. They are well-matched, without question.

Before the book, before the restaurant, Conlon and Lo had an underground supper club called X-Marx. X-Marx was not Macanese; Conlon and Lo cooked everything from veal brain salad to barbecue quail consommé. They cooked a lot of dinners, a few “comatoast” brunches and over the years created some weird takes on Asian food. They’ve actually said the phrase “Greek-Namese” out loud.

But Macau was always there, marinating somewhere in the back of Conlon’s brain. He credits an article food writer Margaret Sheridan wrote for Saveur in 2001 with piquing his interest. In the piece, Sheridan laments the limited demand for Macanese food, noting, “this wonderful hybrid cuisine is now an endangered species, living on in only a few restaurants, a smattering of residences, and the memories of the colony's elders.”

Macau made sense for Conlon and Lo. Conlon is Portuguese-American, and grew up in Lowell, Mass., in a community among several ethnic groups, including Asian-Americans. Lo is Chinese-American, and grew up making dumplings with her family in Chicago before spending time in India and Italy. If Conlon and Lo had a baby, it would be part Chinese and part Portuguese, along with myriad other world influences, just like Macau.

Conlon and Lo first visited Macau in 2011, while on a vacation/food research trip. “We realized, this is us,” Lo says about the few hours they spent there as a daytrip from Hong Kong.

If you don’t know where Macau is, well, get in line. Macau is a tiny independent territory, less than 12 square miles, off the Pearl River Delta in China. It was a Portuguese territory from the 15th century until 1999, when Portugal returned it to China. Its food is most broadly described as a mix of Portuguese and Chinese, with influences from Malaysia, India, South America, Thailand, Africa and other countries. Today, Macau is an international gambling destination. James Bond hangs out there between secret missions.

Conlon and Lo were not international spies, just a couple of chefs on vacation who thought Macau sounded interesting enough to warrant spending a few hours there on a day trip while eating their way through Hong Kong. They wandered the streets, got pretty lost, then, hungry beyond belief, stumbled into Riquexo, a subterranean cafeteria run by Dona Aida de Jesus—the Julia Child of Macau—and had a meal that changed their lives.

"It was food that was new, but made sense to us," Conlon recalls. "We ate feijoada and linguiça, but could taste the Chinese influence in them. It was Portuguese food but she used curry and tamarind. She is incredible; she's like the last cook doing this food, and it's in this cafeteria. It blew my mind."

Fat Rice Photo: Galdones photography

Opening the Restaurant

Conlon and Lo returned to America, their future shifted. They started to play with Macanese dishes on their X-Marx menus, but even as they decided to take the plunge and open a restaurant, they still didn’t know that it would be Macanese. They knew the food would skew Asian, and that it would be more authentic to their vision than to tradition.

“We’d done a couple of Macau-inspired dinners with X-Marx; we thought it was a nice balance between our own respective cultures,” Conlon says. “When we were building the restaurant, we knew we wanted to incorporate our own cultures, as well as do some of the stuff we had learned in China, but doing Macanese food was never something we intended, really, until a couple of months before we opened.”

As they found a space, worked through construction, found furniture from Lo’s grandparents and equipment from failed restaurants on Craigslist, they thought about names and concepts, but couldn’t decide on anything. And the work of building a restaurant meant they always had something else to focus on. But it wasn’t until they were almost ready to open that they settled on Macanese food, and named the restaurant Fat Rice, after one of their signature dishes, arroz gordo.

“We had ideas of what we wanted to do with the restaurant, to cook our own respective cultures, and some of the other cuisines we had experienced while traveling,” Lo adds. “I had spent some time in India, and Abe had traveled to Brazil. We enjoy these flavors. Where Abe grew up, he was surrounded by a lot of Southeast Asian food, so it’s always been of interest to him. So we were like, these are all the things we like, this is what we want to do, it’s kind of Macau. It was a difficult thing to commit to. People weren’t going to know where it was; it was going to be confusing to them. But this is a restaurant about us, and what we want to do. We wanted to commit to Macau and share it with people."

“Macau gave us a really big box to work within,” Conlon notes. “The food brought a lot of the world cuisines that we loved—South America, Western Europe, India, Africa, Asia, Japan, China—together.”

“Macau gave us a really big box to work within. The food brought a lot of the world cuisines that we loved—South America, Western Europe, India, Africa, Asia, Japan, China—together.” Abe Conlon, Fat Rice

Hugh Amano, a cook who had collaborated on a few X-Marx dinners, came on board as sous chef. Amano had been bouncing between a few cooking jobs while writing a food blog, “Food on the Dole,” and he and Conlon and Lo seemed to get each other. He helped fine-tune the Macanese-inspired menu, and get the restaurant open. Fat Rice opened in late 2012, on a Chicago street corner far away from any trendy restaurant districts, and with no sign. Just a few months later, Bon Appetit named it the #4 best new restaurant in the country. In the accompanying article, restaurant editor Andrew Knowlton described eating at Fat Rice as, “like a far-flung episode of The Amazing Race, except here all the players go home happy.” Next

More about the Making of a Cookbook

- Log in or register to post comments