The Making of a Cookbook

Finding an Agent

There was talk early on about doing a Fat Rice cookbook; a few food writers who ate at the restaurant told Conlon and Lo they should do a book.

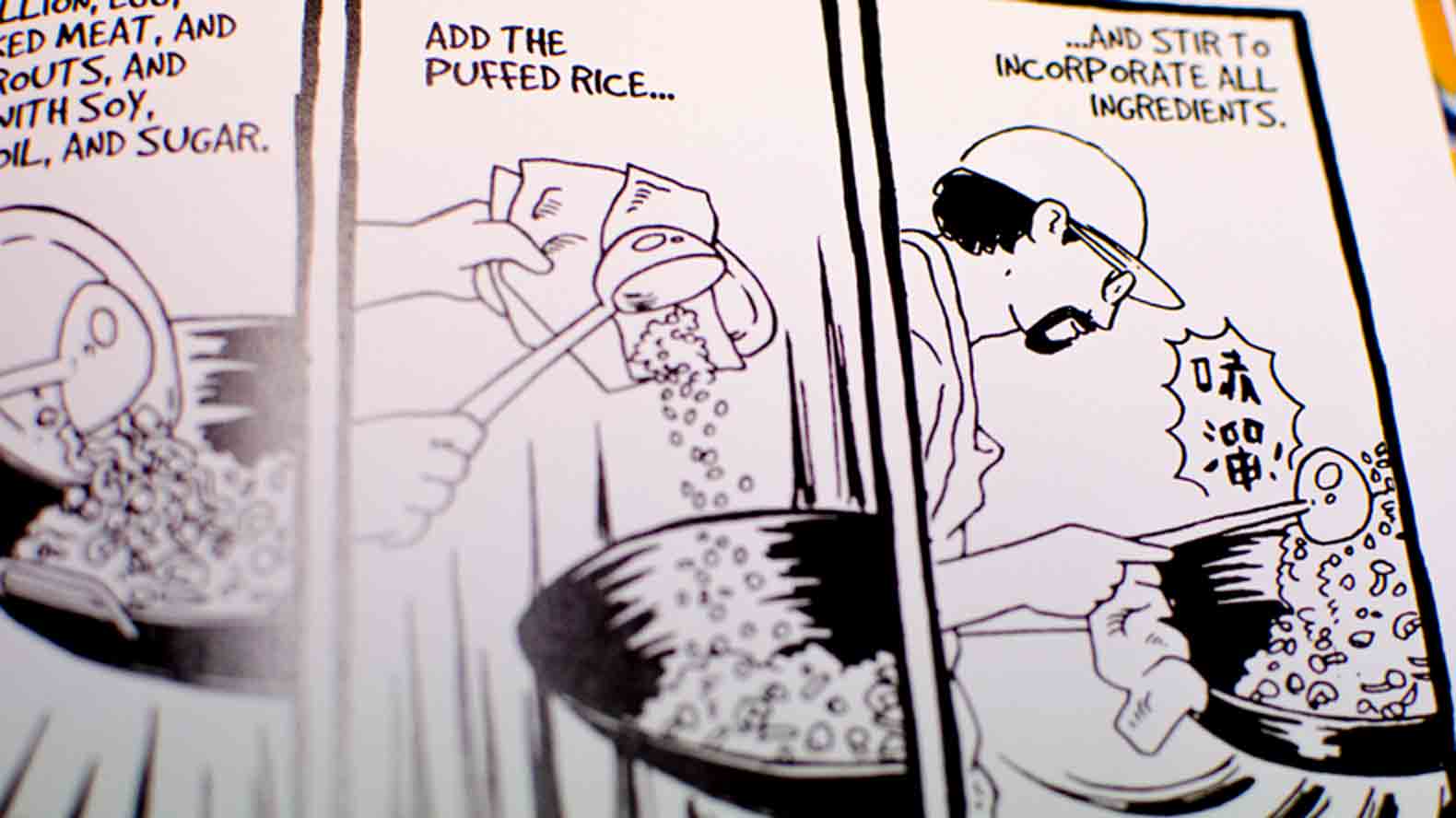

“After a few people said it to us, we were like maybe we should write a book,” Conlon says. “Maybe that was stupid, but saying ‘no’ can be a regretful situation, and you don’t know it’s regretful until it’s too late. We thought it was the right time, and a good opportunity. We have all these Macanese books, and all this information that most people are not privy to. These books, they’re not in print, or you can’t find them, or they are written in Portuguese. They are very hard to get, the pictures are not the greatest. The other thing that was an interesting correlation to me is that we are seeing all these fused concepts, like the Kogi taco truck, or Kimski’s. People say this is such a new thing, and I think the cool thing for us is that it's been happening for years in Macau.”

“After doing all these dinners, and knowing how much work went into each one, and how much stuff we created with very little documentation, moving forward, we wanted to be able to document what we were doing," Lo says. "Food is fleeting: You make something, it’s eaten and it’s gone. We wanted to be able to share it with people, not just at the restaurant.”

“We were like, OK, we will do this, but how do we do it? Do we need an agent, or what? We really didn’t know anything.”

Adrienne Lo, Fat Rice

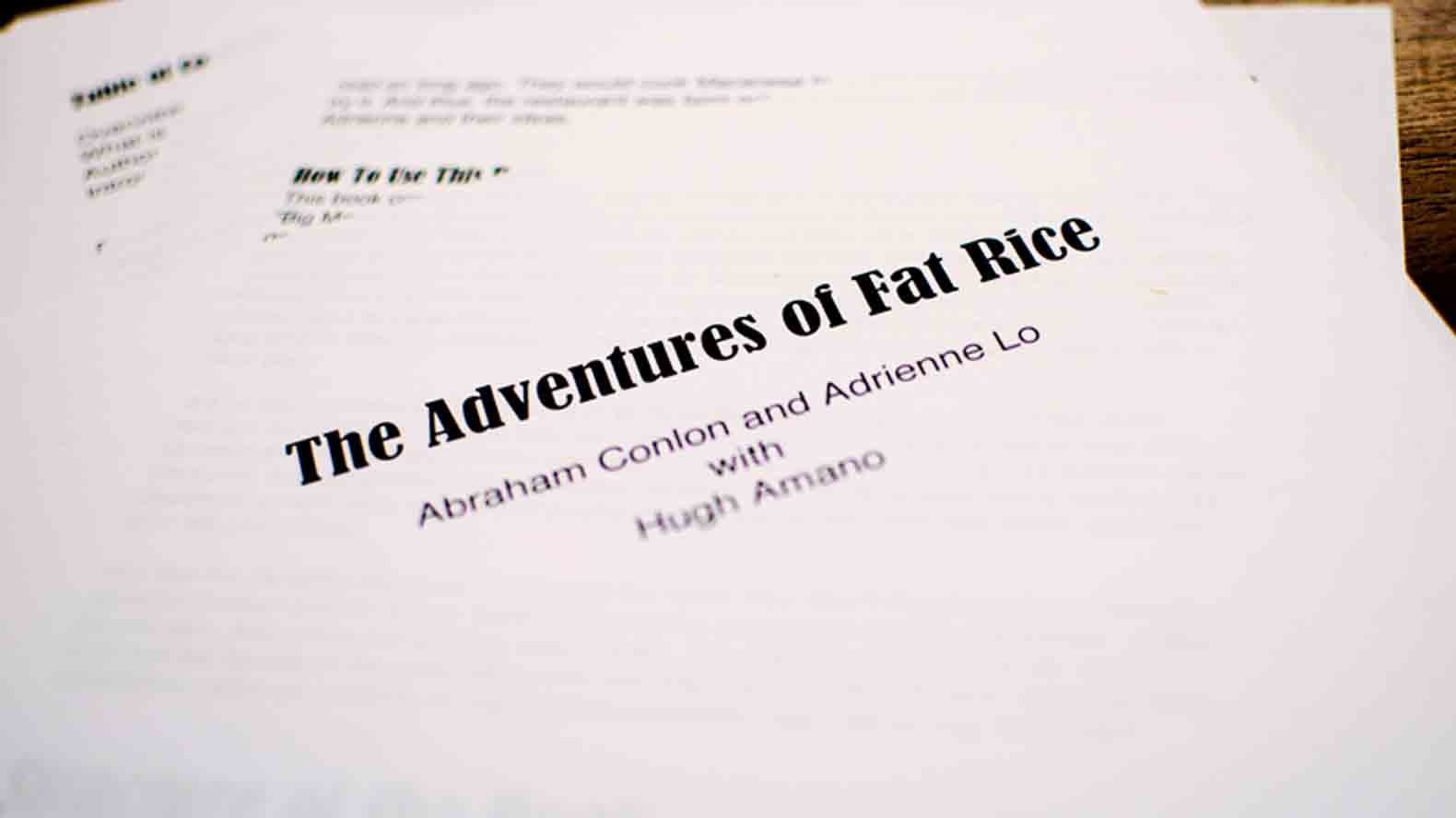

For Conlon and Lo, it was clear that if they did a book, Amano would be key to making it happen.

“Hugh was a good friend of ours, and talked about writing a book someday,” Lo says. "He helped open the restaurant and had been through a lot with us and understood where it started before Fat Rice opened,” Lo says. “He was there for the inception, back when we were saying, ‘What are we going to do with this restaurant?’ Hugh wrote the recipes, the training manuals. He knew us, he’d worked with us. There was never really a consideration of doing it without him.”

The idea was definitely in the air, but they had to figure out how to do it.

“We were like, OK, we will do this, but how do we do it?” Lo recalls. “Do we need an agent, or what? We really didn’t know anything.”

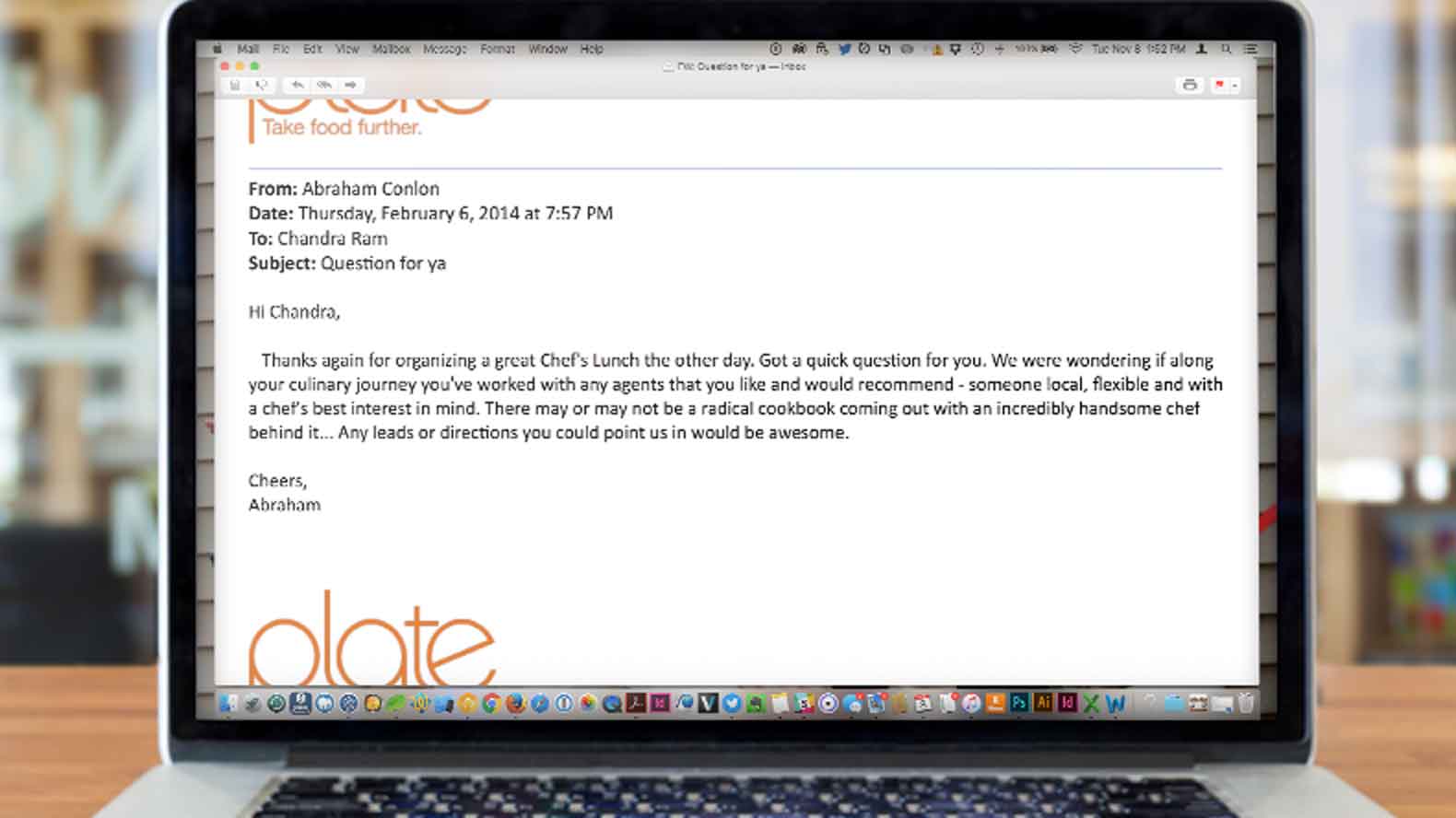

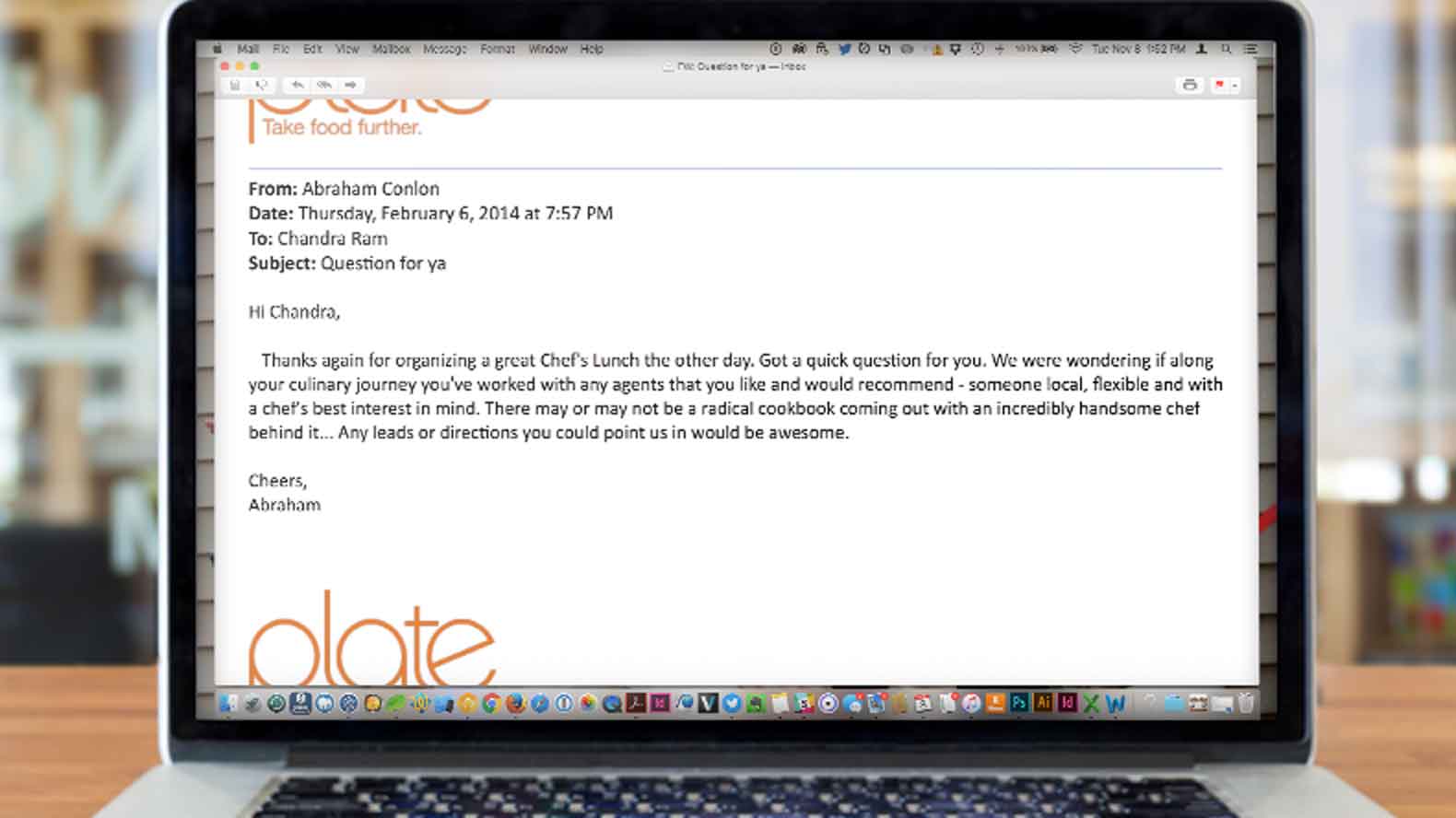

An agent from New York expressed interest in representing them, but they weren’t sure if it was the right offer. In February 2014, Conlon and Lo emailed me about finding an agent. They were among of dozens of chefs who have asked me how to get started with a book, and I didn’t think their chances were that much greater than most other chefs. Because getting a book deal is almost impossible for most chefs, especially those who aren’t in New York.

How Publishing Works

Why? Blame digital. Book publishing changed dramatically somewhere around the time all of us started reading books on our phones instead of trooping off to the store to buy a printed book. Today, you can buy an e-book for as little as a dollar on your phone and have it delivered to you in less than a minute; it’s a lot easier than finding time to go to a bookstore and picking up a hardcover book for $30 or $40. In the publishing business, e-books are referred to as a “disruption,” meaning that while they create new opportunity, they also displace an established (and profitable) market. Add in some fairly brutal pricing wars between Amazon and publishing houses, and you can see why there has been a lot of talk in publishing circles about whether e-books would eventually kill print. Except with cookbooks, which is ironic, since anyone can jump on Google and find a recipe for just about any dish in the world, for free and in less than four seconds. But for some reason, we still want to hold a cookbook in our hands, we want to flip pages, browse photos and read recipe notes. If anything about cooking or publishing is left to be romanticized, it’s cookbooks.

When you scroll through the best-seller list, you’ll see dozens of names of publishing houses. What you probably don’t realize is that there are only four major publishing houses in the U.S: Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, Simon & Schuster, and Hachette Livre. Most of those other names exist as imprints, which are branded divisions that specialize in specific areas and market books to specific buying audiences. Clarkson Potter and Ten Speed Press are two of the most prestigious imprints, but are both owned by Penguin Random House, a company that came into being when Penguin and Random House merged in 2013.

Conlon and Lo likely had no idea of any of this when they first started thinking about writing a cookbook or how it would impact whether they would get a deal; hardly anyone understands the particulars of book publishing. Which is one reason why finding an agent is key.

Connecting with an Agent

Chefs create books as an art form. Publishers publish books to make money from an art form. Agents bridge the gap to make it happen. Cookbook agents are some combination of sales reps, negotiators, scouts, matchmakers, emotional babysitters, collections agents, cheerleaders and coaches. In short, they have a high tolerance for crazy. Agents know the publishing world the way chefs know food, and they can spot a bad book deal at 10 paces in the same way chefs can tell that your truffled risotto was made with fake truffle oil and not the real thing. Agents know when Italian cookbooks are selling well and when the industry is overrun with them. They know that certain acquisitions editors are fans of Asian food, baking, Asian baking, or whatever. They know that every chef thinks he or she has a book to write, and that every chef thinks his or her book should be featured by Oprah. They are the people who have to explain that you might be a great chef with a fabulous restaurant, but without a great story behind it, you are not a great prospect for writing a cookbook. Or that if you have a chance, where the need lies; whether your book need to appeal to restaurant/chef types or people looking to make easy weeknight meals. It’s no surprise that on her website, book agent Lisa Ekus offers a long list of what should be included in a cookbook proposal, along with a line wishing prospective authors good luck; that part of her site saves her a lot of time that would otherwise be wasted meeting with chefs who will never make it through all the steps in the process.

Agents make their money by taking 15 percent of the royalties a publisher pays an author. Which is why some chefs think they should try and get a deal without an agent. The problem is that without an agent, your chances of getting your book proposal in front of a publisher are almost zero, and even if you get a deal, you are most certainly going to be low-balled by that publisher. Most publishers are based in New York City, so it’s hard to get their attention unless your restaurant is also in New York City. And even if your restaurant is in New York, is it big enough (or small and cute enough?) to get their attention? Is it in Manhattan, where everyone goes for business, or in Brooklyn, where everyone goes to feel cool? Is it one of five Korean noodle spots on the block, and if so, is one of the other spots owned by David Chang? Because, at the end of the day, is the customer base enough to warrant printing 50,000 copies? Will your book make money?

There are a few big names in cookbook agenting out there. Kimberly Witherspoon represents David Chang, Yotam Ottolenghi, Anthony Bourdain, Ruth Reichl and Gabrielle Hamilton. Ekus, based outside Boston, reps a mix of restaurant chefs and food writers and bloggers, including Kevin Gillespie, Virginia Willis and Natalie Slater of the vegan baking blog Bake and Destroy.

Compared to Witherspoon and Ekus, Chicago-based Amy Collins is an upstart. Collins was born and raised in Arkansas, but that said, she is no soft-spoken Southern lady. She specializes in working with chefs, and as a matter of survival, does not suffer fools. As Chicago’s restaurant scene has blossomed over the past ten years, Collins’ proximity to and relationships with the city’s chefs has established her as a rising star in the publishing world, and she’s brokered deals for James Beard Outstanding Pastry Chef Mindy Segal and for former Fat Duck R&D Chef Kyle Connaughton. And when Conlon emailed me to ask if I could recommend an agent, hers was the name that came to mind. [Editor's note: Collins does project work for Plate.]

“It was only four or five pages, but when I read the proposal, I was like, ‘Oh my God. This is solid gold.’ I was into it. Way into it. I could tell what they had and how valuable it was.”

Amy Collins, Squid Ink Literary Agency

“When I initially heard from Abe and Adrienne, I was really excited, but I’d heard there was an agent in New York who was interested in them, so I knew there was stiff competition to sign them.” Collins says. “People who sign with me rather than a large agency do so for a reason. I'm not corporate in any way. I don’t walk in the door in a suit. I more or less dress like the chefs; I look like them. We hang out at the same dive bars, we’re living our daily lives in similar ways. The other advantage I have is time. I work for myself, so I don’t have a boss telling me I’m spending too much time with a client. Some authors want an agent in New York in a power suit. But I’ve found that authors who want a relationship that feels more like a friendship and the matching of equals tend to choose me. It would be what felt best for them.”

Collins, Conlon and Lo met and talked about the restaurant, the book idea and what it would take to write a book.

“I have never interviewed with a chef without having eaten at the restaurant several times beforehand,” Collins says. “But at the time, it was at least a two-hour wait to get in to Fat Rice; there was a line to get in by 5 pm, and it was a really hot summer. So this is embarrassing, but I hadn’t eaten there yet, and I didn’t have time to go before the interview. Of course, one of the first things Abe asked me was if I’d eaten there. He is not the the kind of guy you can lie to: He would’ve asked me what I ate, I wouldn't have been able to bluff, and he would have nailed me to the wall. He can sort the wheat from the chaff pretty quick. So I told them I hadn’t braved the lines and they set me up with a reservation for later in the week.

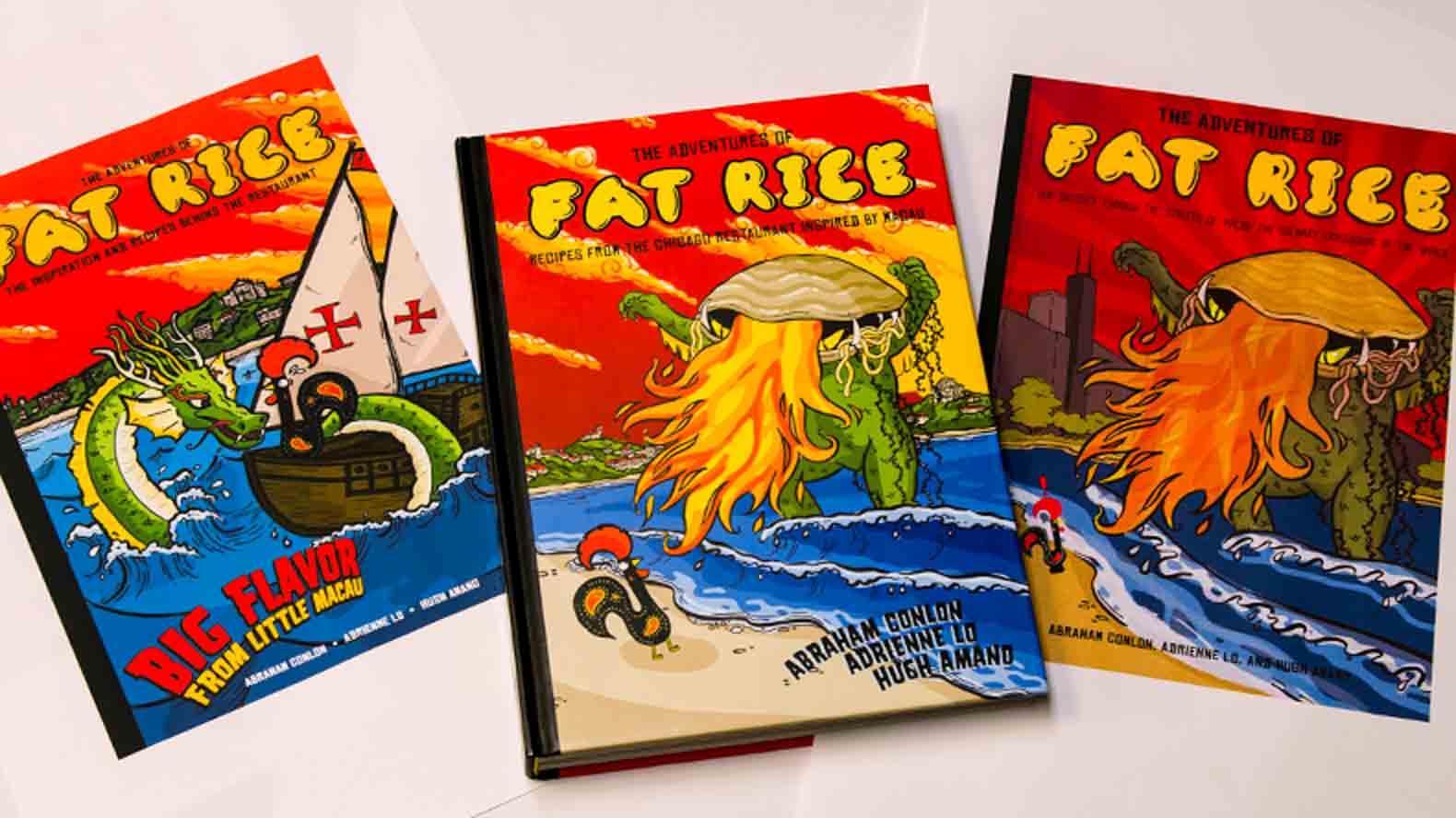

“We met for an hour," she continues. “They got to know me and we talked about what they wanted to do in the future and how a book would fit into those plans. They had already started working on a proposal. It was only four or five pages, but when I read it, I was like, ‘Oh my God. This is solid gold.’ I was into it. Way into it. I could tell what they had and how valuable it was.”

Collins ate at Fat Rice that weekend. “At the end of dinner, Abe came out and we talked a bit,” she recalls. “Then he grabbed the bill of his baseball cap, smashed it around like he does, did a long pause and said, ‘Adrienne and I have decided to go with you.’

“It was a matter of connections,” Conlon says. “That’s how we do things anyway. You get the right vibe from people, and you get that sense that they are on your team. Amy had rep'd Mindy Segal, who is a good friend; she came highly recommended. She was excited about the project already. Signing with Amy was a no-brainer for us.”

About the Advance

Collins wrote up contracts for Conlon and Lo, and a separate one for Amano, who would be paid out of the advance she would be able to negotiate for them.

An advance is all the money most chefs get from their books. I've heard of chefs getting advances too low to even cover the cost of photography, and of chefs getting a hundreds of thousand dollars—the range is all over the place. It's an advance payment against the book’s future royalties, and is calculated by a number of factors like the manufacturing costs and how many copies the marketing department thinks will sell per sales figures based on similar titles. The editor creates a P&L statement based on all those factors and that’s how the amount of the advance is calculated. In the end, it’s basically a gamble on how well the book will sell before it is relegated to those $1.99 discount tables in bookstores.

There's an old joke, attributed to literary agent H.N. Swanson, that the most lucrative type of writing you can do is a ransom note. Writing a cookbook is not a way to make money, unless your name happens to be Ina Garten or Martha Stewart. Most chefs break even or lose money on their cookbooks, once they figure in the cost of their time, paying for a writer and photographer, the cost of ingredients for recipe testing and everything else that goes along with it. It has to be worth it for other reasons.

“I was worried, to tell you the truth, before I met Amy,” Amano recalls about signing the contract. “You picture an agent being flashy about the money, kinda pushy. Amy is not like that at all. My concern was how well I would be represented; I was the third tenor, if you get the Seinfeld reference—everybody knows the first two, and then I was the other guy. Abe is a huge support to me; I wasn’t worried that he would take all the credit, but he’s the one people are interested in. But when I met Amy, it was clear that she had my back as well. She’s a pretty strong supporter of co-authors.”

Things moved quickly from there. Collins worked with Amano, Lo and Conlon to turn their ideas into a full proposal, work that would take several months. But they didn’t have months before having their first chance to get in front of a publisher. The International Association of Culinary Professionals (IACP) was hosting its annual conference in Chicago, and some of the biggest people in cookbook publishing would be in town. And even without a complete proposal, Collins needed to seize the moment and sell this book. Next

More about the Making of a Cookbook

- Log in or register to post comments