The Making of a Cookbook

Writing, Recipe Testing and Photography

Back in Chicago, they had to focus on recipe testing and photographing the food. As most chefs know, even in the (unlikely) case that you have recipes written down, they probably aren’t ready for prime time. Even when they are cleaned up, they aren’t ready. Restaurant recipes are in proportions too large for the home cook, they don’t include much if any information on the method and assume you know how to cook at a pretty high level. Even if they have a lot of detail, they don’t have the kind of detail a home cook requires.

Recipes for a cookbook are very different. First, each publishing house has its own style, so the recipes have to be formatted to match it. The ingredients have to be in the order they are used. If you use three-quarters of a cup of oil in the beginning, and a quarter cup of oil at the end, you can’t just tell readers to get a cup of oil; you have to be specific. Your readers don’t know the difference between a blond and a brown roux, they don’t know to soak dried mushrooms and strain out the dirt, they may not even know what sauté means. So you have to be really specific, and you can’t assume anything.

For Conlon, picking the recipes for the book was tough. He had classic Macanese dishes on the list, dishes that were Fat Rice twists on a classic, and dishes that weren’t Macanese in flavor but were very popular in Macau.

“I feel a huge responsibility to the people of Macau," he says quietly of the food in the book. “There are not many of them, so it’s important for us to be true to them and to not dilute that, and to have the tightest information as possible. We do add our own twist, our own style, but we have to say that this is what we understand to be traditional, or this is what we do based on availability. Or we had this other experience that influenced us and we changed something and now, it’s a Fat Rice dish.”

“I feel a huge responsibility to the people of Macau. There are not many of them, so it’s important for us to be true to them and to not dilute that, and to have the tightest information as possible.”

Abe Conlon, Fat Rice

Amano’s experience cooking at the restaurant made the project much easier.

“A fair amount of the recipes were developed already,” Amano says. “I’m fairly organized about recording recipes. But when I left and the restaurant took off, the capture of recipes wasn’t as strong as it could have been, and there was a lot of culinary expansion. Abe is always moving; he’s always progressing. In the restaurant, dishes can change all the time. But for the book, there has to be a finish line. You have to finish and hit 'send.' That was a good learning point for all of us, especially Abe.”

A key part of success for a book's recipes is having them tested, and by regular people with regular kitchens. Your sous chef will read a recipe that is missing salt and automatically fill in the blanks. But your reader will make the recipe, and later complain that the dish needed salt, and what were you thinking?

"Once we got into position where we had captured the other recipes, the current chef de cuisine, Eric Sjaaheim, did a lot of that work,” Amano says. “He was a huge support, not only to the restaurant, but to the book and to me. You have all of this creation coming from Abe, so to have a solid maintenance type of person as far as the recipe writing goes is perfect. Otherwise, Abe would hand me a greasy stack of receipts, with recipes scrawled down on the back, maybe in English.”

They had to divide and conquer to finish the huge amount of information they planned for the book. Lo focused on running the restaurant, and pulled together the book's section on ingredients and recipes that were building blocks.

“That was huge,” Amano says. “Some of the recipes in the book are her family recipes or influenced by family recipes. We have a lot of historical reference from her family. How she grew up making and eating pot stickers, why they taste like they do, that kind of background info. She could tell us if the dish looked right, what this dish actually had in it, if we still put the red pepper in it. That was key.”

Lo’s parents stepped in to help test some of the recipes.

“Everything had to be tested,” Amano says. “I did some of it myself at home—it’s important to do it on home cooking equipment—especially with woks, where you aren’t going to have as much heat as you would in a restaurant. Abe did some at home as well. We had this grand plan to have other people test stuff, but it was more work that it was worth. Adrienne’s parents tested a lot; they were hugely helpful with that.”

Photographing the tacho in a snowbank Photo: Dan Goldberg

At the Photo Shoot

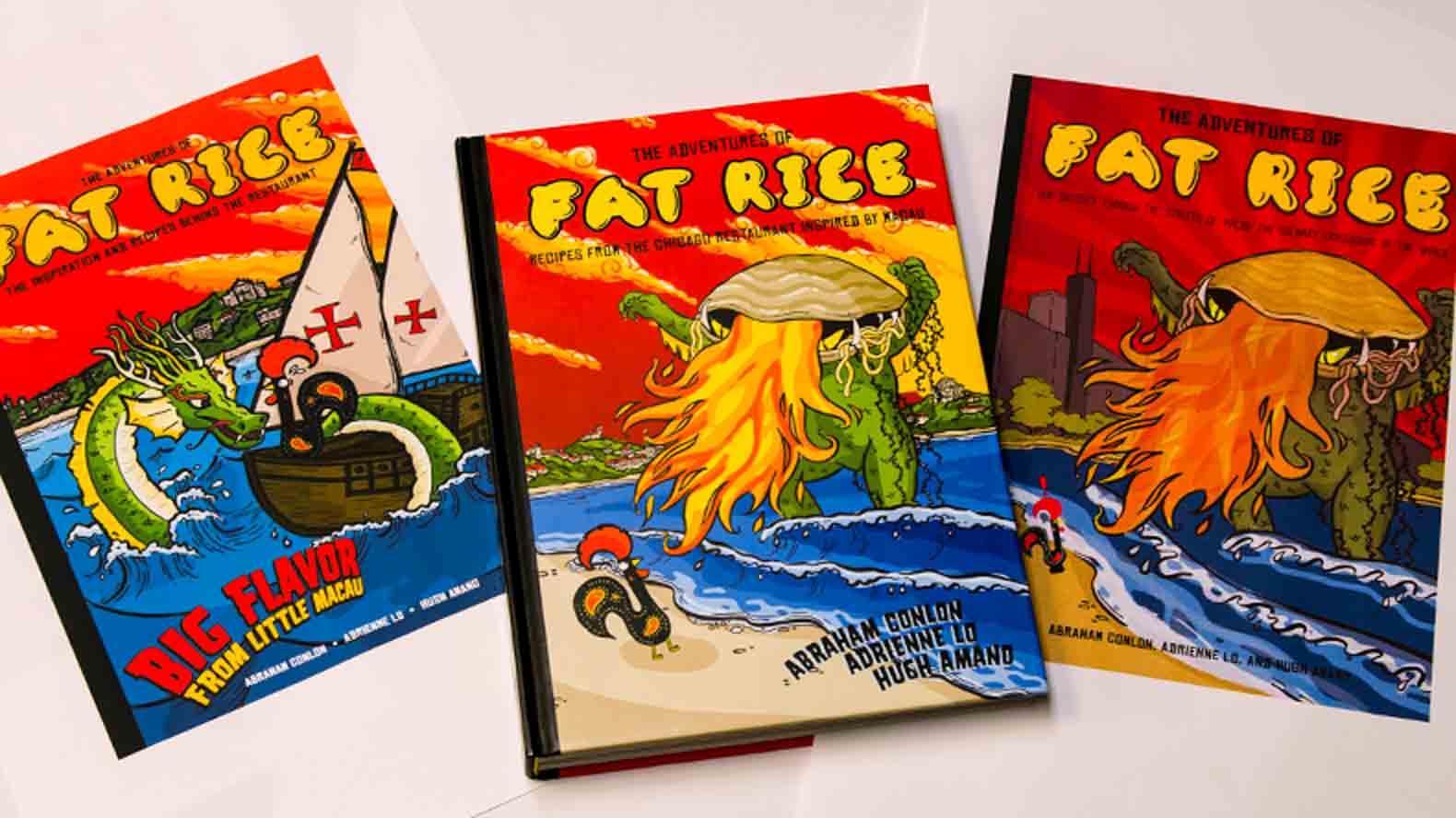

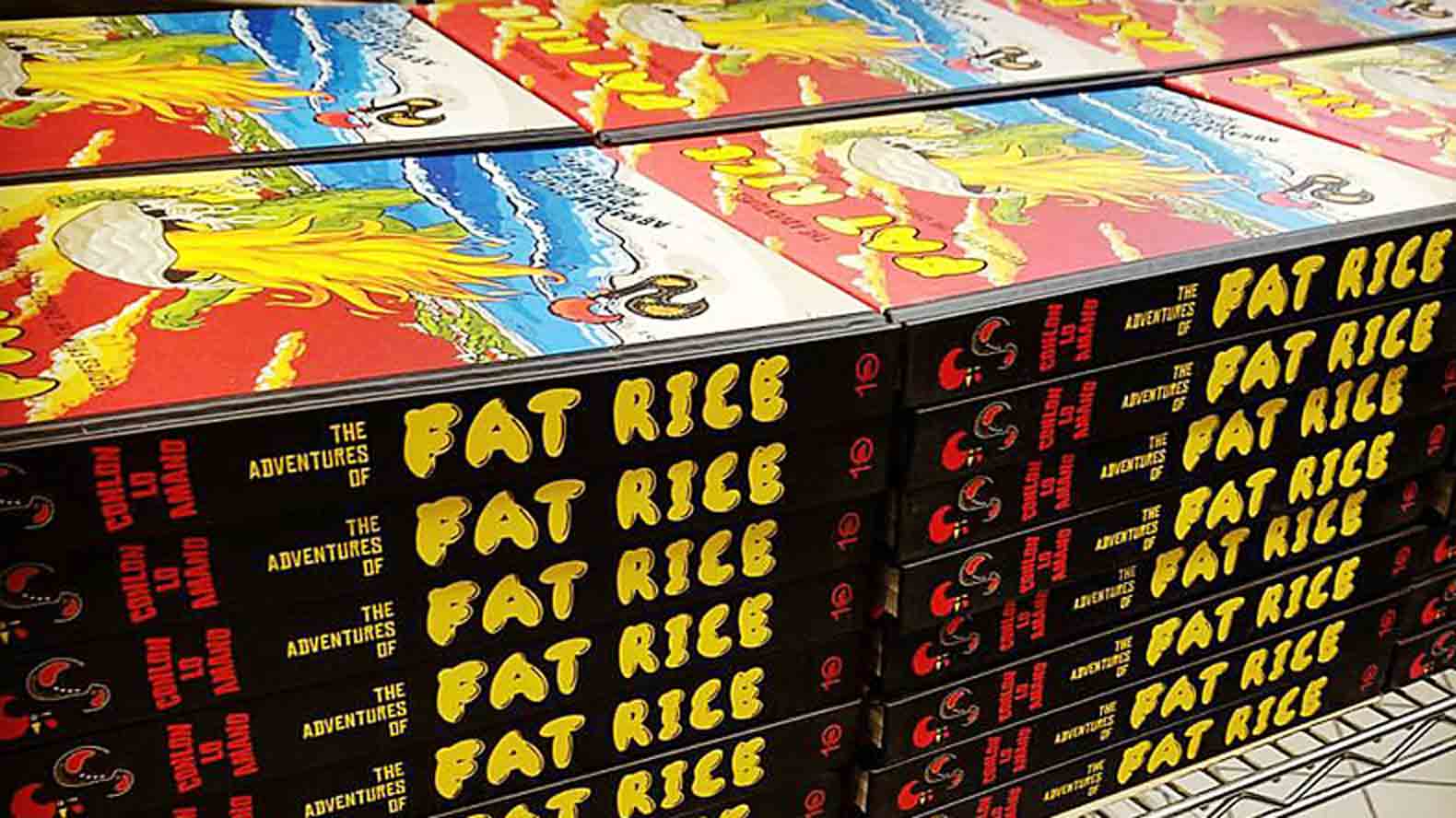

By December, they were ready to the studio food photography at Goldberg’s studio. The quality of the food photography for a book like this cannot be overstated. Big, beautiful pictures of food are a big part of why people buy print cookbooks. And having convinced Ten Speed to invest in location photography in Macau and then studio photography only raised expectations for what they would produce.

“The photography is one of the most transportive elements of the book,” Timberlake notes. “This is a hybrid between a regional cookbook and a restaurant cookbook. A lot of the recipes are taking Macanese preparations and using Chicago ingredients. Or taking a dish and giving it a Macanese twist. The photos had to be great.”

Plikaitis flew in from California to work with the team on the overall look. Goldberg brought in a prop stylist, plus an assistant, a digital technician and a producer for the 10-day shoot. Conlon and Amano prepped and produced the food. There was no food stylist; like many chefs, Conlon wanted to style the food himself.

“Abe is a chef in the truest sense; he’s the chief,” Amano says. “He was the one directing a lot of it from our end. There were group discussions, but I have to say, the way that the pictures look is because of Abe’s vision. Everything had to be what it was; nothing shellacked or fake or anything.”

“The work felt very avant-garde,” Goldberg says. “We were trying new things for every shot, and trying to push the limits on every picture. All of us have strong personalities, so we sometimes clashed, but we tried to put our egos aside. We did six to 10 shots a day, so we didn’t have a lot of time to waste. We’d do a couple of versions of each shot; they evolved as we went on and grew into something different. Sometimes we’d say, ‘Let’s do a three quarter angle,’ then look at it and say 'Maybe we should shoot this way instead.' I love every picture in the book, and I don’t often say that.”

That freedom wasn’t without risk.

“I remember we were shooting the diabo,” Plikaitis recalls. “This was a shot where we put something down on the plate, then kept building and building and building the dish, and Dan’s shooting and shooting and shooting. And Abe’s intense, and he’s like, ‘Nobody talk!’ Then he’s like, ‘OK, it needs to be on fire.’ OK. Meanwhile, there’s this fabric scrim next to it. He pours rum all over this masterpiece and lights it up. But unfortunately, the flames jumped off onto the floor, and we’re all just waiting for the scrim to catch fire and Abe just starts dabbing it out, and we were like, ‘OK—fire averted.’ In my head, I was like, ‘Let’s not do that again, Abe.’”

The shots varied depending on the mood they were going for. For the curry crab recipe, the team tried to recreate one of their most memorable meals from Malacca.

“We had curry crab in Malacca in this tiny hole-in-the-wall place,” Goldberg recounts. “Abe managed to score the last few crabs, which is something I wouldn’t have had the courage to do. We were eating them, and my face was yellow, a greasy mess. There was an outdoor bathroom to wash off, and someone would come by and sell you package of Kleenex. So we set it up like we were back in Malacca, sat on the floor, drank beer, ate for a bit, then I would take a photo of the table. We shot it in stages. It was a lot of fun. We tried to recreate our experience, the flavors and smells, and bring them to the book.”

“Let me tell you how quickly duck blood coagulates on a plate. That shoot was my first time with duck blood.”

Kara Plikaitis, Ten Speed Press

For the tacho, or Macanese boiled dinner, Conlon wanted to pay homage to one of his favorite classic cookbooks.

“The tacho picture is one of my favorites,” he says. “It’s straight out of Taste of France, where you have a dead rooster, a slab of bacon, a bottle of old crusty Burgundy. We shot it in the snow. Why not?”

“We had been talking about that shot for a week,” Goldberg says. “We went to Chinatown and grabbed some ingredients. It was snowing on the way back, and Abe said we should shoot this in the snow. It has nothing to do with Macau, but it’s December in Chicago, so let’s do it. Abe has some crazy ideas. We went and shot it outside in the back, and it worked."

“We wanted it to be true to them; that’s the fun of photo shoots. Let me tell you how quickly duck blood coagulates on a plate,” Plikaitis says, drily. “That shoot was my first time with duck blood.”

For Plikaitis, the shoot was a chance to spend some face time with the team, and make sure their shared vision coalesced.

“Abe was kind enough to take us all out to dinner one night, me, Amy, everyone from the shoot. We closed down the restaurant on a Thursday night. Then we went to Lost Lake, had drinks, and back to the restaurant. To be in the space, see what it was all about, to be able to talk Amy, to be with the team, that’s my favorite moment, when you can relax and understand what it should be, and how they want it to evolve. You get it—OK, this is the web we are going to weave. It’s important.” Next

More about the Making of a Cookbook

- Log in or register to post comments