Chefs and Restaurants

A Show-Stopping Platter

The only time the noise level seems to diminish during the Bocuse d’Or is when a Crucial Detail platter makes the rounds. Martin Kastner of the Chicago design firm famous for creating the serviceware at Alinea was asked to design Team USA’s meat platter in 2015. When it was presented, a hush fell over the grandstands. “I remember thinking this is either really good or really bad,” Kastner recalls. The response proved positive; Tessier’s platter took top prize for the meat course.

“Martin is really the fourth guy on the team,” Tessier notes. “He’s spent an incredible amount of time with us, detailing out multiple pieces to help bring the food to a level that’s not only more precise but also efficient. To do the level of food we’re trying to do in the time we have is really difficult, and he’s been a huge asset to getting us to another level of execution.”

Kastner agreed to design Team USA’s platter in 2017, but not until he met Peters and knew they were compatible.

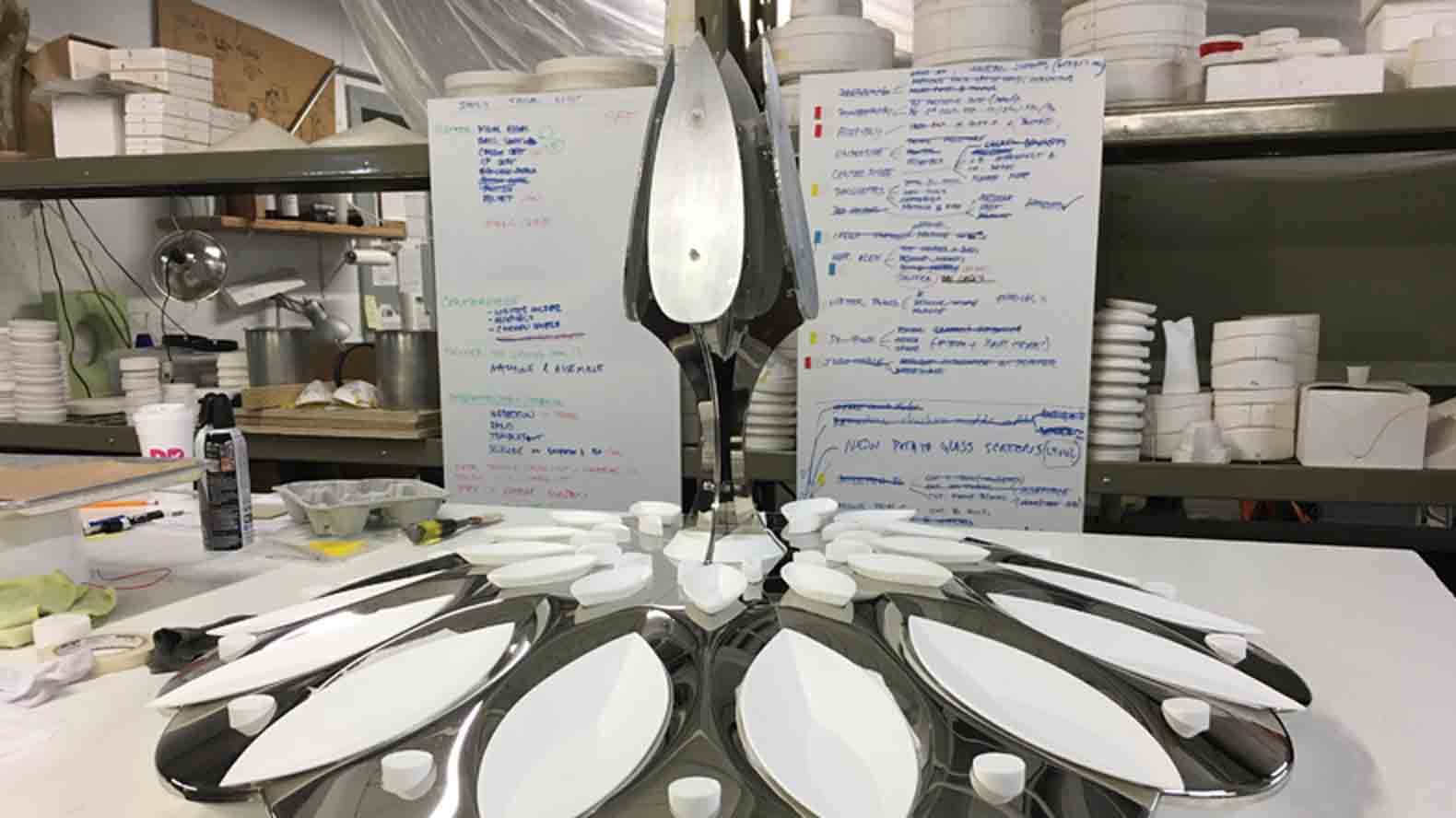

The platter comes together Design: Crucial detail

“It needs to be a person I find a common language with,” says Kastner, who wanted to get a sense of Peters’ vision via mood boards they created for food and design. “I try to connect the food and the platter in terms of form and function, so we’re trying to remove anything we don’t need. My approach to design is somewhat negative. I’m from Eastern Europe, so I’m a little bit like, ‘what do I not want it to be?’ So that’s how I establish my parameters. And from there I think about more positive stuff. But it’s an ongoing conversation with the chef.”

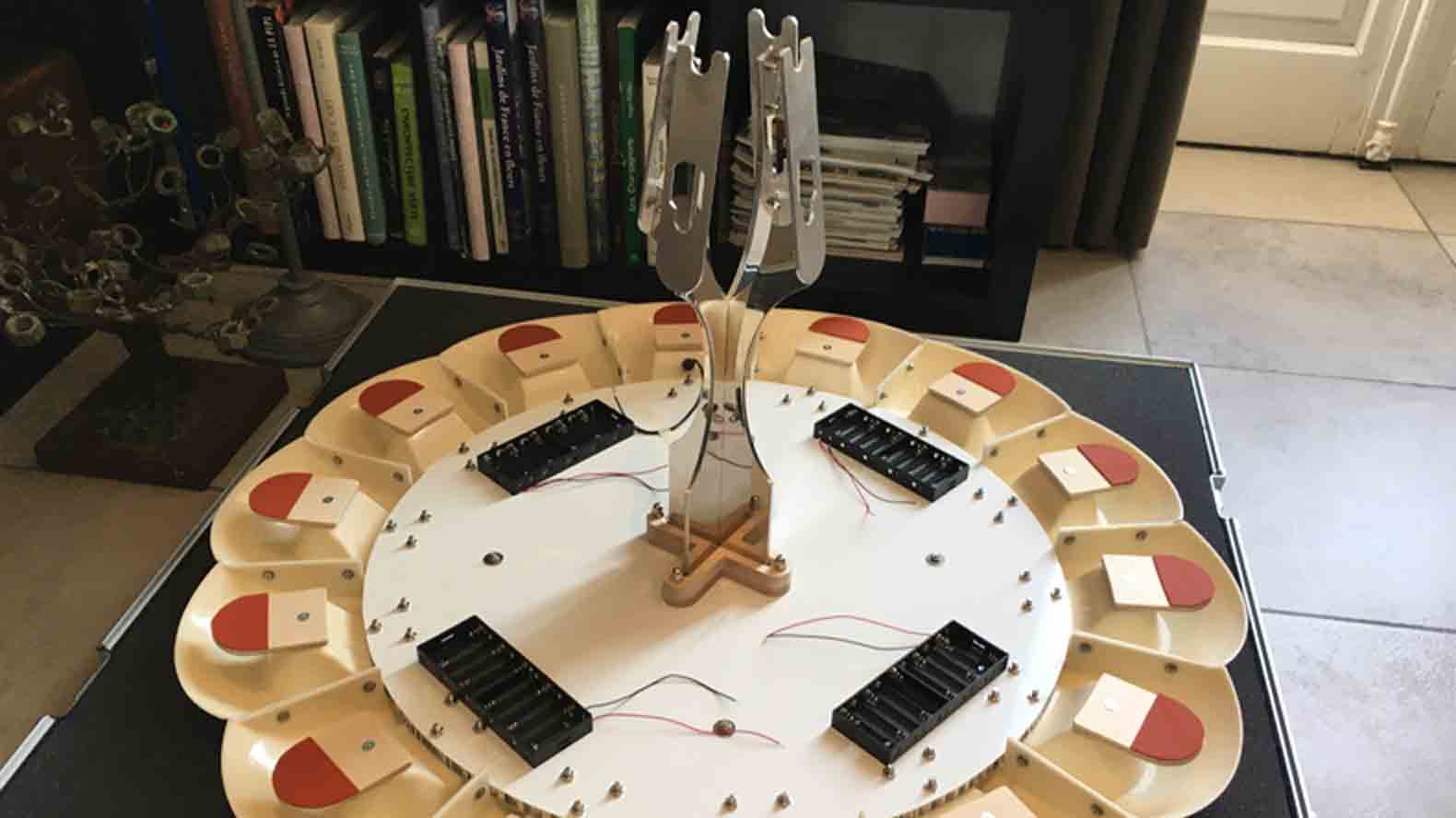

Kastner and Peters went back-and-forth about the platter’s design and functionality for nine months, making sure to adhere to the competition parameters. Not only is there a size limit, but the platter can’t weigh more than 40 pounds, while being large enough to hold 14 tasting portions for the judges, and serve as a vehicle to showcase the food. It also must be easily carried for a good 10 minutes past the judges. And since the food has to be hot, they had to figure out how to keep the heating elements hidden.

“We made the platter hollow, so we were able to put all the heating components inside,” says Kastner. “It’s a part no one would see. The guys would power the heat by switching on the circuits.” Kastner used an ultra-lite honeycomb material, and added holes to the large centerpiece to further reduce the weight. He also designed finger grips on the bottom to keep hands from interfering with the top surface (one of his pet peeves).

But even the most copacetic collaboration between chef and designer means nothing once the TSA gets involved. Kastner’s plan was to hook up the heating elements and circuit board inside the bone china and silver platter once he got to Lyon, but the TSA was not having it.

“Everything was pulled apart so it wouldn’t look like something dangerous, but the TSA still removed the box,” he laments. With just a few days to the competition, Kastner found himself running all over Lyon looking for relays, diodes, transistors, capacitors and resisters. “Soldering a kit like it’s 1985,” Kastner posted to Instagram, showing the mess of shop-class-worthy electronics he had to rebuild the night before the competition.

Time-saving tools

While the platter gets the fame and glory on competition day, Kastner says he was more excited about the custom tools, gadgets and molds he created that stayed behind the scenes but bought Peters and Turone precious time.

Martin Kastner shows Turone how to work the carrot shaving attachment. Photo: MEG SMITH

“With Phil, I spent a lot of time [observing] his process,” says Kastner. “I asked him where he spent his time and what he could improve. That’s why we came to the conclusion to make tools—they are just as important as the platter—to improve efficiency.”

In the end, more than a dozen tools made it to competition day, like a quick-release mixer attachment that helped shave carrots down to a cone in seconds.

“That tool saved us an hour,” recalls Turone, who worked on the carrot garnish for the meat platter. “Before, we had to sit and cut them all with a knife, and he created a tool that shaved them down in five seconds.”

Kastner made silicone molds Peters used to create perfect linear indentations on the chicken breasts, as well as potato presses that gave the potato glass (translucent domes that tasted like salt and vinegar chips) their perfect round shape. He also designed paper cloches that served as presenting pieces for the vegan plate.

“The idea is that you’re trying to make it as experiential as possible for the judges—but not get in the way,” he says. He initially wanted the cloches to be made of parchment but “we couldn’t get it to obey,” so he settled on velum, which had a similar look but more structure.

The patterns were made for the cloches, but all 60 pieces couldn’t be finished until they arrived in Lyon—and were folded by hand (taking over an hour each), mostly by Mimi Chen, who got to accompany the team to Bocuse after winning the Young Commis competition in 2016.

“Phil jokingly asked, ‘why are we doing this?’” recalls Kastner. “I was like, it’s something we can try here, where time has a different meaning than in a restaurant. You wouldn’t get to try it anywhere else, you wouldn’t have the time, so let’s just do it.’”

“The idea is that you’re trying to make it as experiential as possible for the judges—but not get in the way.” Martin Kastner

Ultimately, they were worth the effort. The cloches, lifted by the servers in perfect synchronicity to reveal the vegan plate, wowed the judges.

And when you’re competing at Bocuse, it all comes down to the impact of that final execution. “We spend nine months working on it and then it’s out of our hands,” says Kastner. “When you’re there, you’re in suspense without the ability to influence the results, so that part’s a little tough.” Next

More about In Search of Gold at the Bocuse d'Or

- Log in or register to post comments