Chefs and Restaurants

Project Blackbird: Expansion

After six years in business together at Blackbird, the partners felt comfortable enough to consider opening a new restaurant … in the beat-up bar just across the alley. Sous chef Koren Grieveson was tapped to lead the kitchen at Avec, the wine bar they opened in 2003 with a more rustic menu and wine list, in a distinctive wood-lined room with communal seating.

Diarmit: It took us six years to open our second restaurant because we weren't these guys who had a successful restaurant for a year and then thought they could go out and do anything they wanted to do. We were very cautious. And then at year six, we were like, we can really do something.

Kahan: I think we really preached humility among ourselves for a long time.

Madia: I think at that time, no one thought communal dining would work, especially in Chicago. But again, we wanted to do something different than what we saw out there.

Seitan: I remember when we were working on the business plan and Paul was talking about what he wanted to do with the food. He wanted to feature rustic cuisine from the sun-drenched regions surrounding the Mediterranean: Southern Italy, Southern Spain, Portugal and France. We wanted the wine to be from the same regions. It would be something completely new. No one was doing much with Southern Italian wines or the Languedoc. Ricky was busy with the construction of Avec, so I took over the wine program. I knew nothing about wines from these regions other than the fact that I enjoyed them. A few years after we opened Avec, I was looking through my notes. I tasted 1,800 wines to create the opening wine list at Avec.

Kahan: Koren was at Blackbird and she talked about her experiences traveling in Europe, and the seed for the idea came from those conversations. She wanted to do super-simple food, very high essence, clean. It was our first move at retaining a quality person by developing a restaurant and doing a concept for them.

Large: I was at Blackbird when Avec opened. They had lightning strike twice: Avec is a game-changer as much as Blackbird. The five years I spent with Koren were at times difficult but successful; I learned a ton from her.

Fultineer: Opening Avec was years in the making. They went back and forth with building negotiations, leasing negotiations, everything. They wanted Koren to learn a new style of cooking, different from Blackbird, so she was in New York for almost six months working with Mario Batali. Things at Blackbird got really stressful at that point. All the owners were spending a lot of time on Avec.

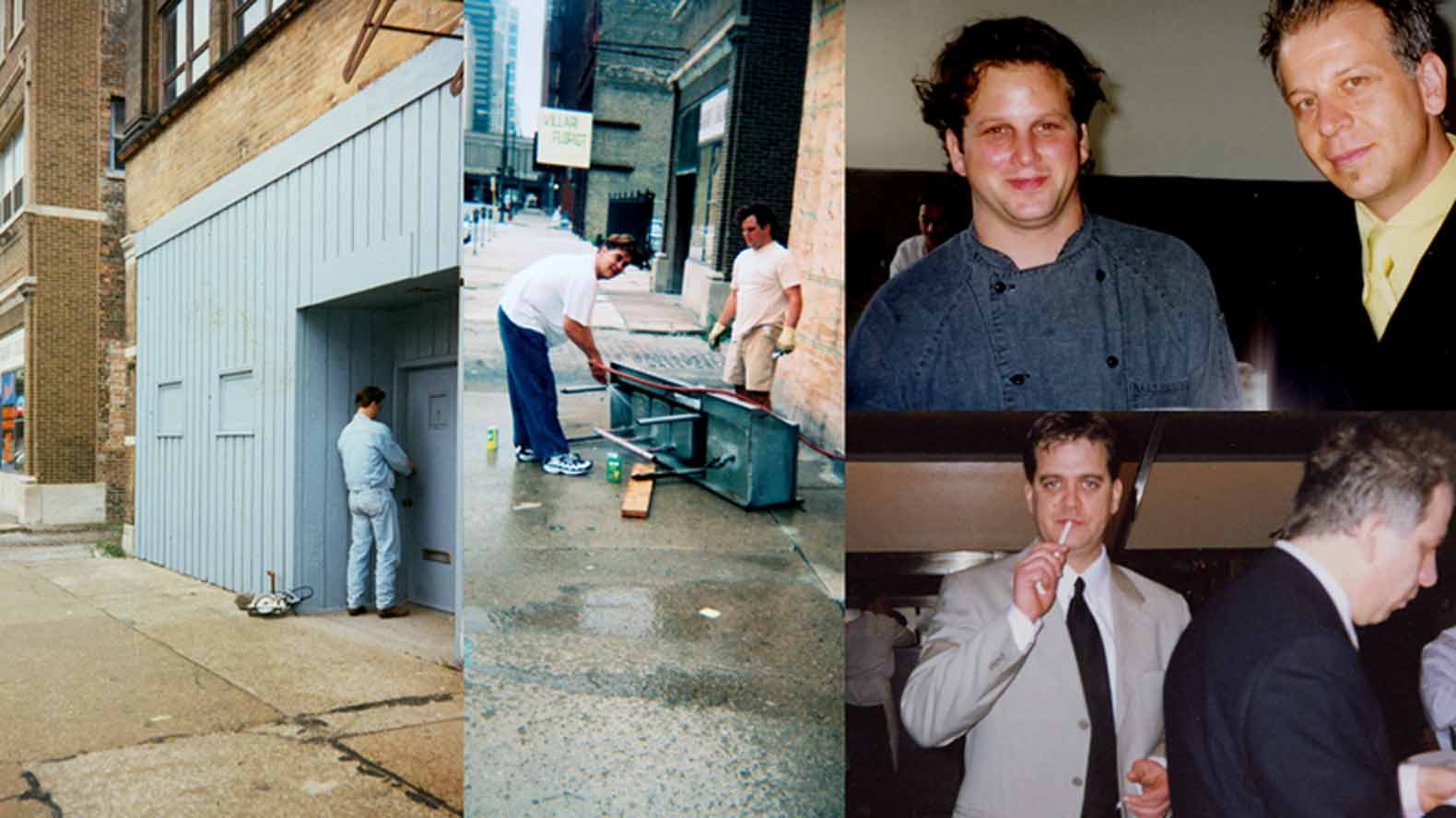

Communal seating a sleek lines were key to the design of Avec.

Jeremy Kittelson: It’s like a family having a new child. Suddenly, that new child gets all the attention, and the other child feels neglected. For a while, I’m not going to lie, there was a healthy tension between the two places; it was competitive. That was more employee-driven, not from the owners. They were fiercely committed to making sure both succeeded and flourished. You want to talk about people giving their all: They would work service at Blackbird, then go lay the floor at Avec. They were truly hard-working guys who did everything.

Bryce Caron: When Avec opened, people in New York were talking about it and Blackbird a lot. Blackbird was what all the cooks talked about; it was where they wanted to cook, and where they spent their money.

Matthew Kirkley: I don’t think any restaurant has meant more to this city since Charlie Trotter’s. Avec completely changed what it meant to be a restaurant in Chicago. The sweeping influence of that restaurant is hard to understate. It was the beginning of the casual chef-driven restaurant. They crammed people into this box with communal seating, which was unheard of back then. And the food was what chefs like, but wasn’t common on menus back then. Wood-baked bread, brandade, charcuterie boards. It was the kind of place chefs wanted to go and eat. That model of restaurant has been aped so many times for 10 years, it’s defined the 21st-century restaurant. So many people have imitated Avec: the menu, the seating, the décor.

Kahan: I was in New York, wasted one night with David Chang, and I said, “I don’t think Momofuku looks that much like Avec.” And David goes, “Like hell it doesn’t. I brought my architect there and I told him to steal it, verbatim.”

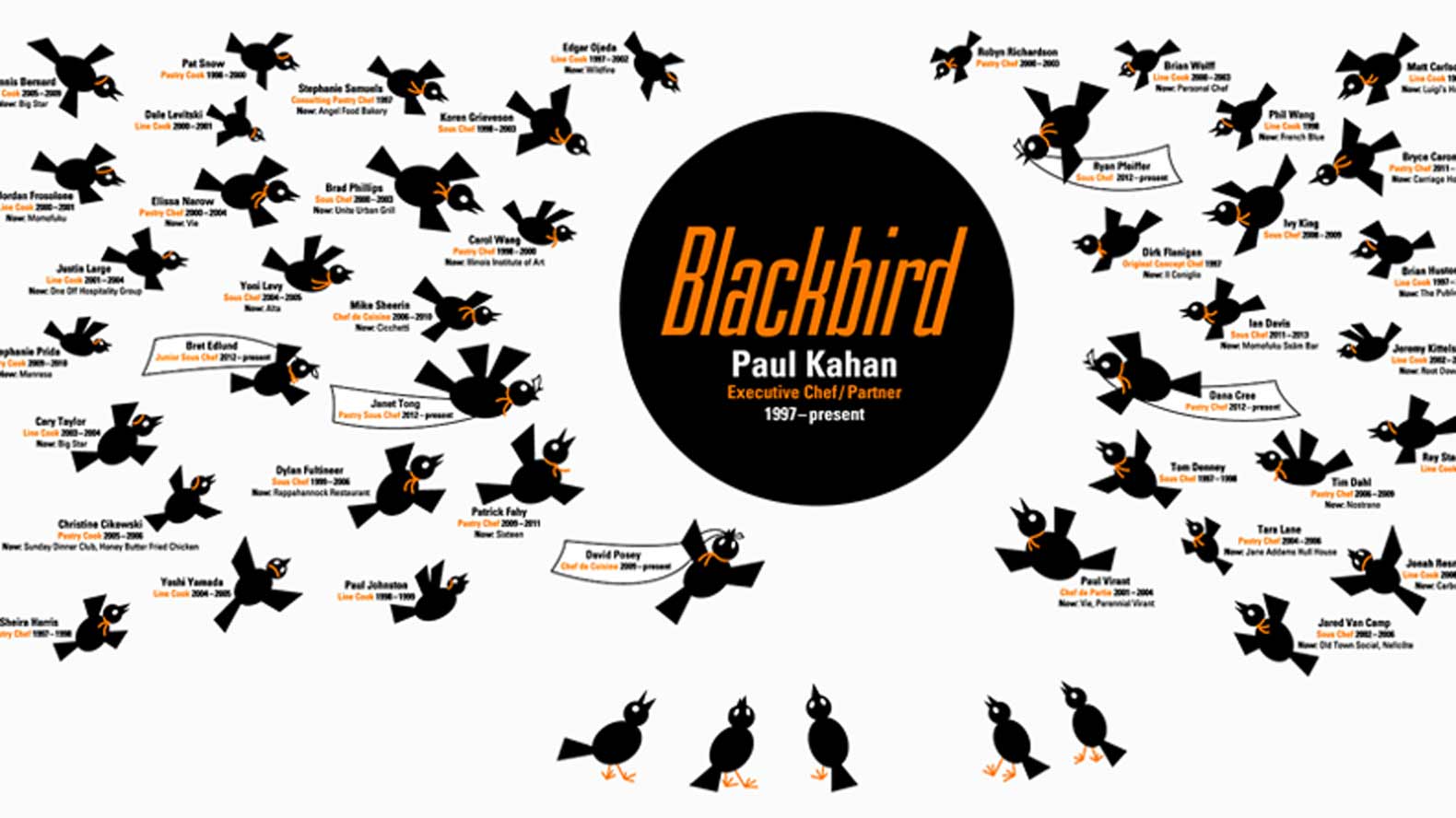

Meanwhile, the kitchen at Blackbird was challenged even more to excel, and it was able to do so with a talented group of young cooks who came together to work as a team.

Van Camp: I had staged at Tru, Trio, Everest and Charlie Trotter’s. I did my stage at Blackbird, and it was a completely different vibe; I had to work there. I went to Blackbird from an executive chef position at the University of Illinois. I was making really good money, benefits, with the potential to stay and make more. And Paul offered me a gig making salads at lunch. When I explained to my dad that I was taking a job at Blackbird and moving to Chicago to make $75 a day, he was upset; he really thought he had messed up raising me. He was like, “You are making this decision and ruining your life.” But he told me years ago to just do something you love. He was worried about me, but I threw his fatherly advice back at him to explain why I had to do it.

We can laugh about it now, but for what you earned at Blackbird, you were compensated so many times over. You learned so much. The fact that we’re still talking about it says so much about it. Paul is brilliant.

Cary Taylor: I don’t think I could have been at Blackbird at a better time. Paul was a working chef; I remember my first day, going downstairs and he was butchering a pig. Dylan [Fultineer] and Jeremy [Kittelson] were sous chefs. Paul Virant was our private party guy, while he was working on opening Vie, and we hit the jackpot, getting to be around one more amazing chef. And we had Koren next door at Avec; she was extremely talented and a great teacher. I got to learn how to make sausage from a James Beard Award nominee and Food & Wine Best New Chef. All those things were the icing on the cake. Jared was the other person who was so important to my career. He was a wealth of knowledge. He was a well-read guy with a lot of experience with food and farming. Justin [Large] was just flat-out a great cook and smart. I was with those guys in prep or on the line 12 hours a day.

Van Camp: The first time I interviewed with Paul, he said, “If you ever want to do a stage, anywhere in the country, I will pay your salary.” It was incredible; no line cook at a small restaurant got a paid vacation. With his reach, I staged at Craft and at wd-50; he made those calls for me. But it wasn’t just the stages; Paul and Donnie said, “Go here, you have to eat there,” and set it up for me. That was my first time in New York. I wasn’t the sous chef at the time, I was just a line cook. I was very, very proud to be working at Blackbird. When I told cooks in New York that I worked at Blackbird, I got respect.

Fultineer: The people I was surrounded by were amazing. Most of the cooks were almost 10 years older than me, and I was given the position of sous chef. Everyone was insanely talented, such an amazing crew. They’ve all moved on to do great things.

Van Camp: It was like competitive sports. If you couldn’t perform, you were left behind. And that fear of not being good enough was … bad. You had to be technically proficient, which was hard enough, and then on top of that, there’s like a creative war going on.

Everybody talks about kitchens being a meritocracy, but usually it’s bullshit; the chef has his favorites and only talks to them. But Blackbird was a true meritocracy. Paul was the only chef I knew who let his cooks create dishes. You could be there for only three months, but you could work on a dish. It was exactly what I needed at that time.

Yoni Levy: I was the guy who would go in super early to get ahead on prep. It was my first taste of healthy competition between cooks. It wasn’t a brigade system; whoever was best and knew all the stations became lead line cook. All of us were pushing ourselves to be better than the person next to us, but it was impossible because the person next to you was so good. There was an awesome camaraderie because of that.

Paul changed everything I thought about food—he opened my mindset. He pushed you to create dishes, for you to succeed in that kitchen. You would say, Paul I want to do a dish with this, and he would say, "let’s talk." Or if you weren’t sure, he’d say, “OK, scallops, apple, celery root—go.” He would get so excited when you created a dish that worked. He loved it. It was that kitchen with great energy, everyone pushing 110 percent. And that starts at the top. He made you feel good about working there. I’d never experienced that before. I’ve never heard of that before. That was so important, because when you’re cooking, you want to make sure it’s at a certain level. You know everything that went into creating the dish, so it’s important to make it the best.

Yoshi Yamada: Paul is a phenomenal editor. He’s a combination of a coach and an editor. Paul would pare inessential shit away from a dish until this beautiful essence was left. He’d reach into your brain and pull out a better, more complete dish. If you’d been there long enough, you could start doing that yourself. He encourages you to refine dishes. That’s part of why people really love working there. If you want to do that kind of creative cooking, if you want to think about food in a thoughtful way, he really encourages young cooks to be part of the process.

Tara Lane: Working on new dishes with Dylan, Jared, Jeremy, Yoshi—it was a constantly evolving sketchbook. Their palates are so good. We would bring things to each other, constantly reworking it and playing with it to get it right. Discovering new recipes, old recipes from farm journals. We were constantly in each other’s kitchens: Can you make this pancake recipe for me? Can you make it sweet? Or savory? That’s when the jowl bacon went on the dessert menu—I would raid savory and they would raid sweet.

Christine Cikowski: Blackbird was where you worked if you wanted to be great, so I worked to get a job there. Tara was into savory elements in her desserts, which was intriguing. That was unheard of to me at the time; I was able to incorporate my savory training into the pastry station. We really loved working with each other. It was a lot of work, but you couldn’t stop thinking about it. It’s a lot of pressure to perform at that level, not in a negative way, but it was like you owed it to the place, and to Paul, and to your sous chefs and co-workers to bring your best every day.

Seitan: When it was time to create the wine program, things came together pretty naturally. Paul was thinking lavender, flowers and deep, earthy flavors. He always did love earthy food. Paul’s palate is so impeccable, I’ve always trusted it.

Seitan has evolved the wine program at Blackbird to include many lesser-known labels from around the world.

Kahan was nominated for the Best Chef: Midwest award by the James Beard Foundation in 2002 and 2003, but did not win.

Large: I remember Paul had been nominated for Best Chef: Midwest and didn’t win. We were bummed. Me, Jared, Dylan, Jeremy; that nucleus, we went to Marie’s Riptide that night and probably drank a few more beers and shots of Jägermeister than we should have. We decided that from that night on, it would be a 365-day push toward greatness, to get that award for Paul the next year. That was all we talked about on the line for a year. It was one of the most intense years of my life, but one of the greatest. You see, Paul included us in everything: successes and failures. When he won, he thanked all of us.

Kittelson: That’s one of the things that made Blackbird so successful, it was a team. There was a real bond between people. You had a swagger working there, but not in a cocky way. It was a bad-ass place to work. There was Charlie Trotter’s, but Blackbird had a different feel to it. When you worked there, you knew you were part of something special.

Winning the Beard award in 2004 opened the door for Kahan to pursue endorsements and book deals, but he was cautious about going in that direction. He began doing more national food festivals and charity events, and networking with other chefs.

Malloy: After Paul won the Beard award, being him became a business. Paul is interesting—he doesn’t want the spotlight. He understands he needs to do it, but it has to fall within his comfort level. I remember having a national TV crew in there one night. The lights were bothering the diners, so the Blackbird guys threw the crew out. A lot of people were interested in Paul, but he didn’t participate in all the events or publishing stuff.

Kahan: For as many times over the years someone has thought one of us was a prick, we give back to the community doing events and fundraisers. It’s really important for us. So much of our time has been dedicated to doing charity events. I want to promote my cooks at these events. You learn a ton from other chefs and you make a ton of friends. My best friends in the industry are some of my best friends in the world, because they are hard-working, good people I met while cooking for charity fundraisers.

Malloy: The cookbook debate was a pain in the ass. Paul saw his friends doing books, and I think that made him want to do a book. He had a definite idea about what he wanted it to be. We would meet once a week to develop recipes and talk about what he wanted to do. But the book that he wanted to write wasn’t saleable, and he wasn’t going to bend. He wasn’t going to tell readers to buy mayonnaise, he wanted to have them make it. He didn’t want to sell out. He didn’t want to do something he wouldn’t be proud of.

Adding to the accolades, the restaurant’s updated review in the Chicago Tribune lauded how far Kahan and the team had come in seven years and the national attention focused on Blackbird.

From Phil Vettel’s 3 ½-star review of Blackbird in 2005 in the Chicago Tribune: “Blackbird is now more than seven years old, and it doesn't show its age. Its mostly-white interior still looks bright and contemporary (the tables are still too close, but I've gotten used to it), and the food, regardless of the season, never fails to excite the senses.”

Vettel: Paul certainly had a very big footprint by then. It had been a while, and I realized that they were getting more attention outside of Chicago, and the review I had in was too old. More and more, I saw chefs following in Paul’s footsteps [in menu development], where dishes change in a more organic process instead of strictly once a season. I wasn’t paying as close attention to the chefs de cuisine and how much Paul was letting them do. I was just putting Paul’s name on anything, and that might not have been fair.

By 2006, as some of his cooks started to move on to other restaurants, Kahan found himself looking outside the restaurant when hiring a new chef de cuisine for Blackbird, new pastry chefs and for the first time, a mixologist. The new team shifted the restaurant’s focus toward modern cooking techniques in savory dishes, desserts and the cocktails.

Mike Sheerin: I was working at wd-50 in New York. I was just about to turn 30, and thinking about moving back to Chicago. Wylie Dufresne went to Chicago to cook for Charlie Trotter’s 19th-anniversary party. He saw Paul there, and Paul said he was looking for someone. And Wylie said, “I got your guy.” He set it up for us to talk, then I came out and staged. I loved everything about the restaurant. I liked the menu a lot; everything was tasty. I wanted to use the techniques from wd-50 and be creative with how I approached the flavors. I thought it was a really great, modern dining spot that could accept that. Not that Paul will ever admit this, but he explained the whole logic to me, and said that they looked at things creatively. To me, it felt like it was going to be a little more creative than it was.

Kahan: Mike came from the outside, and that was a really good lesson for us. He had some really great ideas about how to make the restaurant and the kitchen work better.

Sheerin: Truthfully, I didn’t understand how Paul, a James Beard Award winner, had such a dark, dirty kitchen downstairs. It was one of the things I changed there. I had them put in FRP [fibre-reinforced plastic] and lighting. Before I got there, there was no staff meal; people made sandwiches off the lunch line, and then you’d be out of product. I changed some things.

Fultineer: When Mike Sheerin came in, he brought immersion circulators, a lot of modern ingredients and techniques. There’s always a need to try something new. I don’t think Paul totally loved or adopted that style, but I think he saw the need to try it.

Huston: I went back to Blackbird to hang out and learn from Mike Sheerin. He was really organized and a great butcher. I liked him; he was definitely different. He taught me a lot. He was quick, organized, super-clean, a technician.

Former pastry chef Tim Dahl’s celery root "cannelloni" with white chocolate, pomelo sorbet and cocoa nibs demonstrated a modern direction for the menu.

Tim Dahl: Mike and I started within a couple of weeks of each other. The restaurant still had Paul’s bold flavors and love of acidity, but also Mike’s modern techniques and style. It was a pretty big transition for Blackbird. Mike pushed the restaurant in a different direction.

I worked with both. Paul challenged me: What is the core of the dish? He was always saying, “Take half of this stuff off your plate”; he forces you to tighten your view. I try to do that now with my cooks. You need that confidence that three or four things can taste good, and these 10 extra things are unnecessary. It’s bringing it down to the simplicity of a dish, in a sophisticated way. Making a dish the best it can be with the least amount of excess.

Caron: Tim Dahl made the move to Blackbird and I followed him, so Mike was there six months before I started. I had eaten there a couple of times before. The very first time, I had crispy confit suckling pig. Very classic Paul food. There was corn in five places on the menu because it was corn season. It changed a lot when Mike got there. Mike was completely different from what people thought of as classic Blackbird.

It was a fun time. You had Tim with his traditional pastry, and Mike and his crazy techniques. I was torn between the two visions: how to use the magic white powders that Mike was using and Tim’s traditional techniques with unexpected flavors.

Sheerin: Paul wanted me to get going right away, to change the menu. The first year was tough. Well, there were many difficult years. It was difficult but wonderful. I was trying to understand where he wanted to go with food. He was used to one style, but I was used to something totally different. I think Paul was always about the seasons. He had a more traditional approach to how and why flavor combinations worked. He was definitely more traditional and more business-savvy. He understood what diners were really into and wanted. The truth was, I was used to trying to make interesting, more cerebral food and flavor combinations. We had different points of view.

I think the first two years were really difficult for Paul and for me. It was hard for him to let go, and at the same time, it was hard for me to accept the responsibilities of cooking at Blackbird. It’s an iconic restaurant. I wanted to work on things that kept me involved and moving forward. What I learned from Paul was how to balance the two; feeding the soul and the mind at the same time. When I interviewed for the job, I felt he explained it as more creative when ultimately he wanted it to be more soulful. I was trying to really push myself more than anything, to think creatively, but to also accept Paul’s … what’s the right way to say it? His knack for deliciousness. It wasn’t always an easy relationship. We butted heads on a lot of things.

Kahan: Mike was not the perfect fit. He was someone coming in from outside, and taught us a lot about kitchens that he worked in before, how they would do things. He introduced a lot of ideas and sort of pushed things along, you know?

Patrick Fahy: We worked seven-day weeks, sometimes 16 hours a day. Paul has a knack for nurturing people, promoting people, pairing ideas and flavors. You don’t meet too many people who will nurture you and guide you. Mike, too. I love that at Blackbird, they just worried about making it work. Paul has always had the attitude that the most important thing is the food—it has to taste very good, and that’s it.

Former mixologist Lynn House developed a cocktail program for the restaurant with drinks like the London Calling.

Lynn House: I’ve worked in some great restaurants in Chicago, but Blackbird is the pinnacle of what everyone wants to be. When I met them, I told them the one thing they were missing was a true beverage program, and I was only willing to do it if they committed to a full program. I didn’t want to be a head bartender. If I’m going to come in, I’m going to go balls to the walls and create something that fits in the restaurant. They called 45 minutes later and said I was in; they were creating a position for me. I won’t lie: I was terrified my first month. You don’t want to mess up anything at Blackbird. It was making a big statement in the restaurant community that Blackbird was investing in this position. There was a ton of press from the moment I was hired, so it was a challenge to live up to their expectations.

Sheerin: I don’t think Blackbird was by any means ever fading, but I wanted to give a fresh set of eyes to it, a reason to pay attention again. I thought it should be a prix-fixe restaurant or a tasting-menu restaurant, so I asked to be able to put a tasting menu into play. I felt that more and more diners were into a tasting menu. And with a tasting menu, you start at $100 per person, how are you going to argue with that? I was more into a fine dining culture where we thrived on tasting menus. I felt like it was a great way to really experience a restaurant. It gave diners a chance to see more than three plates, for servers to sell more wine. Paul says he’s not a tasting-menu guy, but he would come in and enjoy a meal with his wife, a longer meal. You’ve got to appreciate that.

Kahan: For me, the dining experience isn’t about 20 courses. It’s about the person you are sitting across from, the whole experience. Great food enhances that and is a huge part of it. I hope all our restaurants exhibit art and soul. To me, a tasting menu is about the chef showing how many teeny herbs you can arrange on a plate; it’s not really what I wanted for our restaurant.

Sheerin’s management style also differed greatly from Kahan’s, creating problems.

Johnson: Mike is probably the only person at Blackbird that I really had a problem with. He was just mean. I thought he needed to go. He was like a drill sergeant; he would pinch people, he would make them do sit-ups, and push-ups. I found out about it through the grapevine and I’m going, “That’s not happening.” Well, I’ll never forget, I had this little guy and he was working there, and he was coming in every day all the way from Indiana. And this kid lasted about two weeks.

He just couldn’t do it anymore because of Mike yelling at him and pinching him. He came over and he goes, “I can’t work for this man.” I said, “What are you talking about?” He goes, “He’s just too mean. He pinches.” I said, “He does what?” He said, “He’s pinching me.” “What do you mean he’s pinching you?” Well, I didn’t know what to think. And I’m like, really? I go waltzing across the street and he was downstairs, and I said, “Wine room! I want to talk to you.” So he went in the back room, and he goes, “What’s up?” And I pinched him. Hard. And I just kept doing it. And I was like, “No more pinching!” He left pretty much right after that. That was bad.

Sheerin: Yeah, it happened. Every single story happened. I grew up in kitchens with pots being thrown at me, getting punched by chefs. Getting yelled at, big time. And then I also grew up in kitchens like at wd-50, where you had to drop and do 10 push-ups. I thought it was fun and made you pay attention, but it was not as appreciated as I thought it would be. I came from a very disciplined set of kitchens. I cherished my time there, but I learned a lot about myself.

House: Working at Blackbird was intense. Looking back, it was very empowering. I felt like I grew up and grew into myself. When you have Donnie, Paul, Ricky and Eddie believing in you, you can’t not believe in yourself. When I put in my notice, I cried for about half an hour. I fell apart and sobbed until I could get it out of my mouth. I cried for two weeks. But I had bar injuries, tendonitis. As much as I loved it, I needed to get away from service; it wasn’t good for me.

Johnson: I remember it was so heartbreaking for me during those years, when people started to leave, because I wasn’t used to that. Everybody worked together. I’m crying, man. I mean, people are leaving and I’m going, “What do you mean you’re leaving after one year? Where are you going?” But now, I’m used to it. They need to grow, and they need to work somewhere else. But it’s kind of nice because they still keep in touch. Next

Blackbird Chapters

- Log in or register to post comments