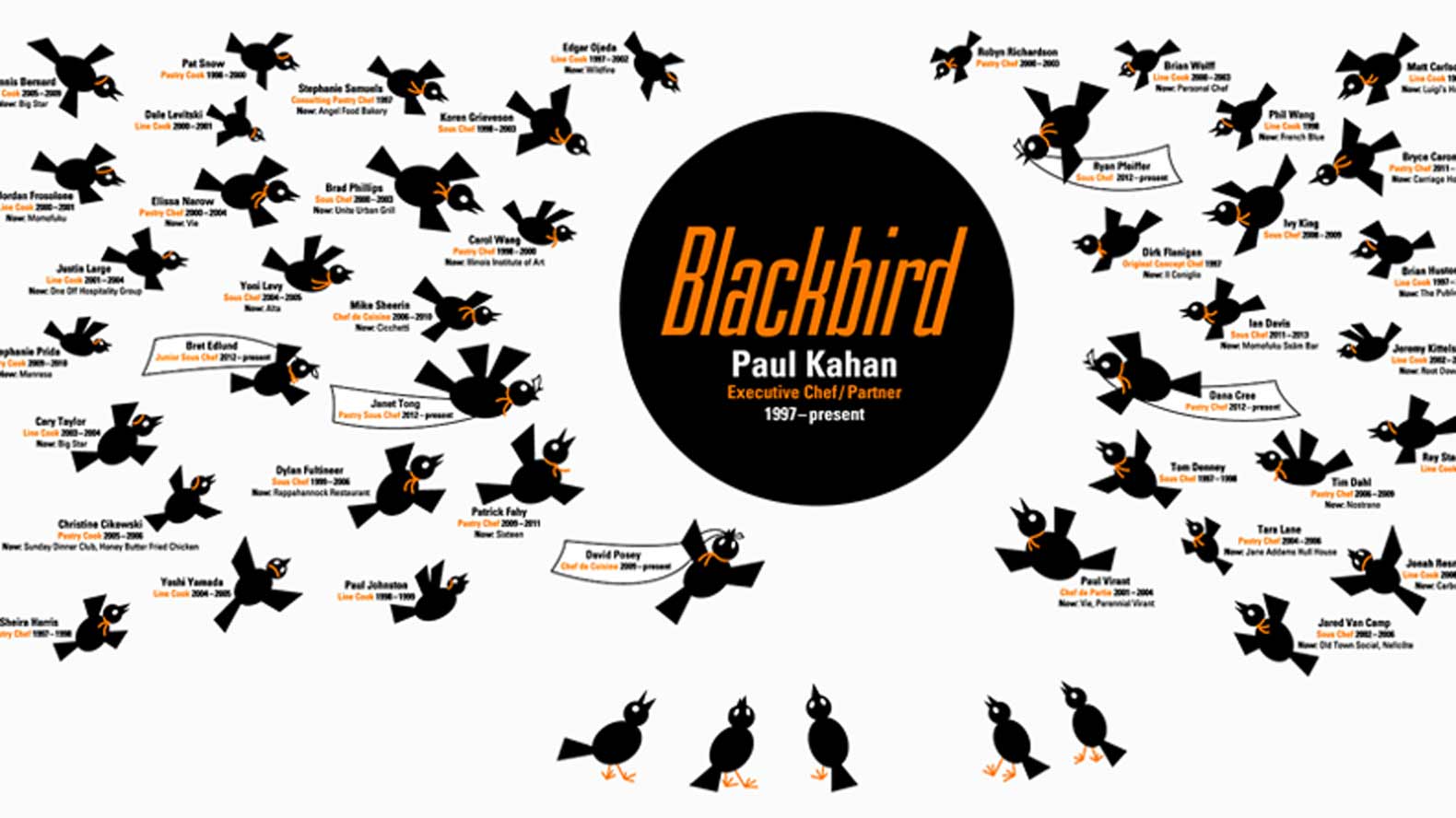

Chefs and Restaurants

Project Blackbird: Opening The Restaurant

Donnie Madia and Rick Diarmit signed a lease on the restaurant space in September 1996, brought Paul Kahan on as chef/partner in February 1997 and brought Eduard Seitan on as another partner later that year. They needed to do two things in order to open: find money and finish construction.

Kahan: When we got started, we didn’t know what the hell we were doing.

Madia: We found an attorney who was going to incorporate us. We didn't know the difference between Chapter S or Chapter C. We knew the lingo, but we didn't know what they were. So that guy played around for like three weeks or so, and I was like, we have to have a document to get this liquor license application going. So we found another guy, and he and I started the paperwork for the liquor license. And then I had a friend who was a real estate agent and had a program on her computer for us to write a business plan, because we were short $50,000 and needed an investor, fast. Like Paul says, we didn't know what the fuck we were doing.

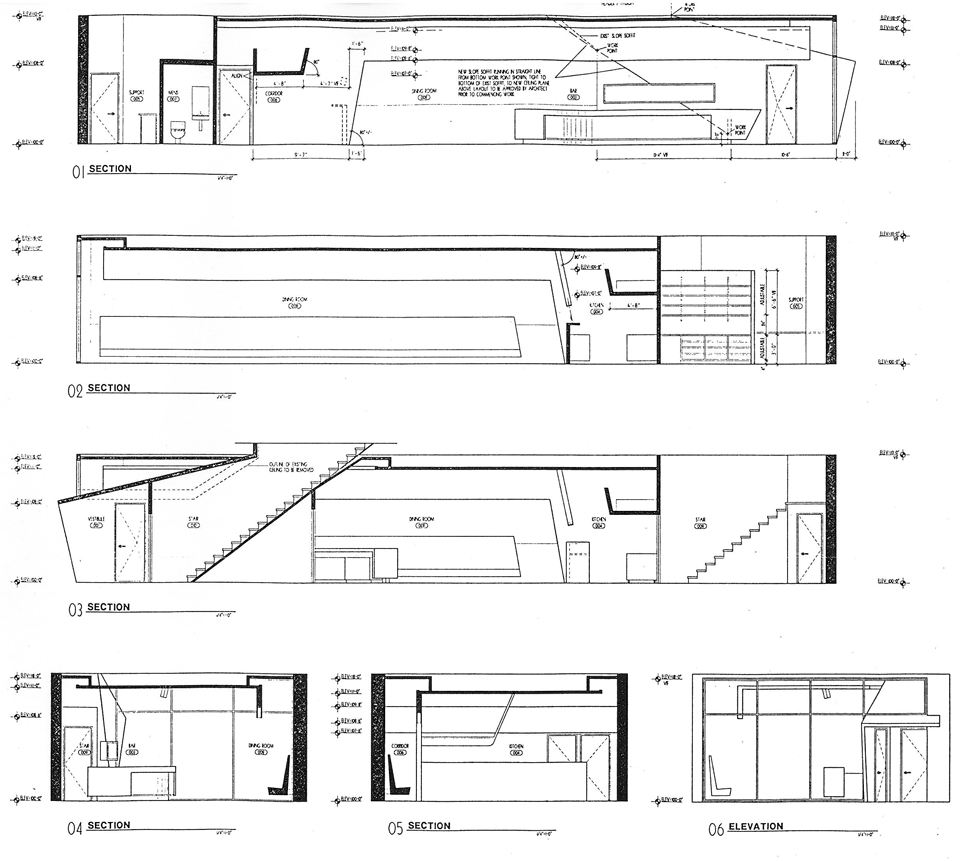

Architectural renderings of the space.

Kahan: I was in the space early every morning, sweeping. I started to develop an understanding of construction; we all did. I would meet with Thomas [Schlesser, the architect] and we’d go over the finishes, chairs, this and that. And then we would discuss how some application would work, you know, the 90-degree turn for the lighting trough, whatever you want to call it. How does a suspended ceiling tie in? He would tell me, “If the contractor does not know how to read the drawings, then you need to get another. You need to get somebody who knows how to read the drawings.” And you know, we had battles. There were many of them.

Madia: We were also dealing with [landlord] Dion Antic and his craziness. He was bringing in shit from all of these other places.

Kahan: Dion took half of the basement for storage. He had a stockpile of crap in the back half of the basement. A wet carpet, ceiling tiles, all kinds of crap. The basement, I think there was a cement floor, but it was so dusty and dirty, it looked like a dirt floor. And I would sweep that almost every day. He was micromanaging us on a day-to-day basis. We met with him a couple of times; he was like the king in his castle. He talked down to us so badly, I think all three of us wanted to jump over the desk and kill him. Right?

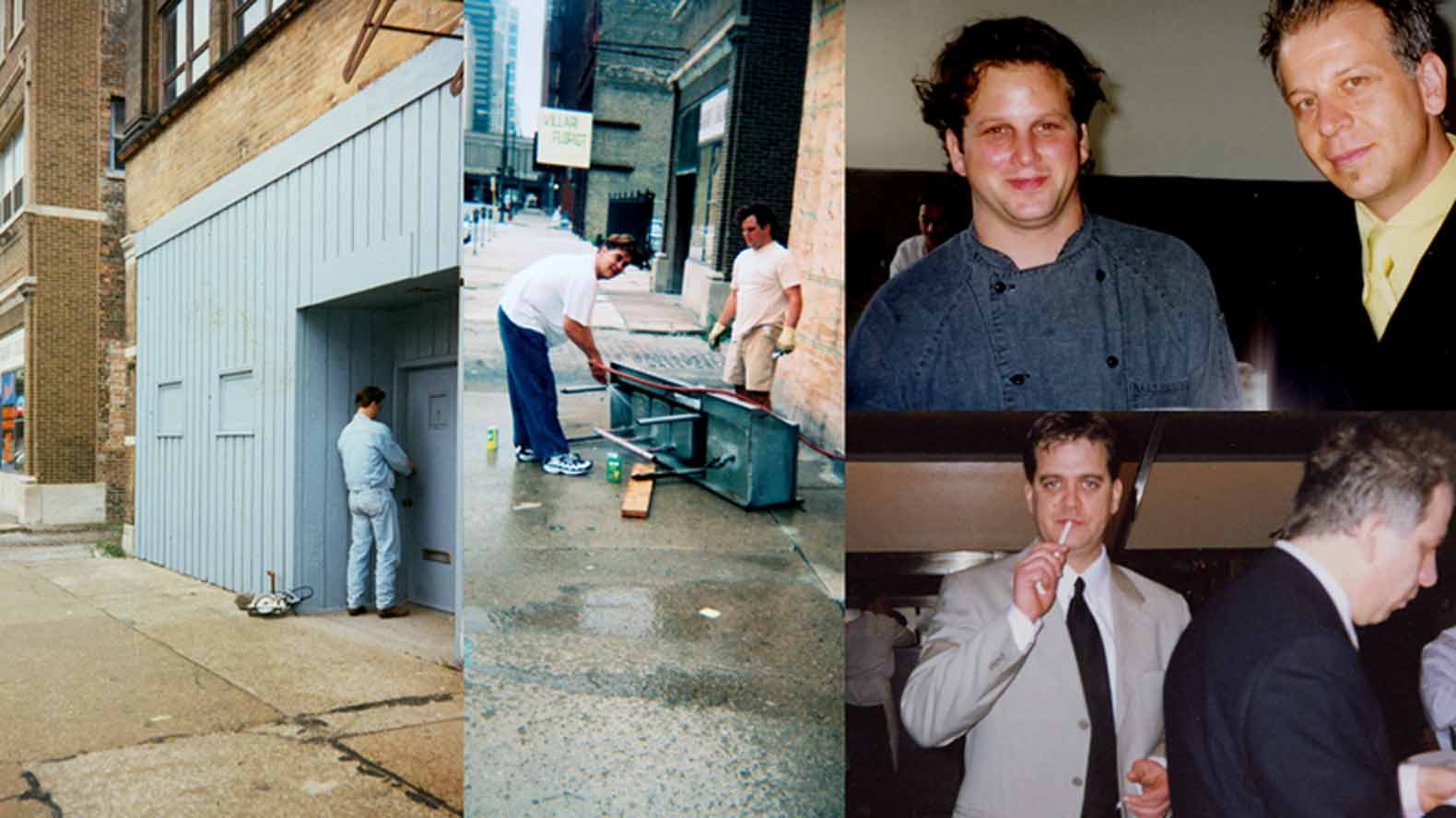

The Blackbird space under construction.

Madia: Yeah. I think I wanted to kill him a couple of times while we were building the space, but Ricky stopped me, thankfully.

Kahan: Dion couldn't find anybody to rent the place upstairs. He had delusions of grandeur. The idea was to rent space to a spa guy, a massage therapist, and they were going to run pipes. He was like, “We're going to have to break through your ceiling in order to get to it.” This is the torment that we would go through on a daily basis.

Diarmit: We're still building this restaurant while this was all going on.

Kahan: There was this one electrician, Ziggy. I just remember his card was like, "My name is Ziggy. I love to party." And he would carry that card around and go, “Ha, ha, ha!” And we’re in the space one day, and Ziggy's hanging from the ceiling with one foot on a ladder, installing the wrong lights in the ceiling.

Madia: He’s got one foot on the kitchen counter, and he's on a four-top, dangling.

Kahan: And Donnie walks in and was like, “That's it—he's out!” He fired Ziggy on the spot. He must have showed me that card 20 times. “Hello, my name is Ziggy. I like to party.” Let's party, baby! [laughs]

As the build-out progressed, Kahan wanted to change the name of the restaurant.

Kahan: I came up with the name one day when I was sitting on my back porch, watching a Cubs game. This was before I knew these guys. I was watching the game and daydreaming about being a chef and owning a restaurant. And the Cubs sucked, so I was flipping through the channels. You know how the Cubs go.

Madia: He only had [channels] 2, 5, 7, 9 and 11 [laughs].

Kahan favored wines from the Rhone Valley.

Kahan: You’re probably right! [laughs] I flipped to public television, and there was a show about wine in Provence, and they were interviewing a little French man, and it was subtitled. He said he had recently planted Merlot in his vineyard, and the grape reminded him of a little blackbird. And that kind of stuck in my head. I thought if I ever had a restaurant—I envisioned [something like] The French Laundry, very quaint, 10 little tables—I thought a great name would be “The Little Blackbird.” So that stuck in my head for a long time, and when we hooked up, we started talking about the name. Thomas’s idea was Menue, with an “e.” Donnie liked it. I just—it didn’t work for me. This was the first of the great Kahan-Madia arguments [laughs]. Donnie hated that name, Little Blackbird.

Madia: I don’t hate anything. Dislike, maybe.

Kahan: Well, you fought against it for a long time. We got to the point where we said let’s come up with 10 names each, and then we said we’d run them by people and see what their reaction was.

Madia: What happened was, Paul and Ricky were upstairs tasting wine, and he was lobbying people like no other person was lobbying [laughs]. I, on the other hand, had things to do during the day, so I didn’t have time to lobby. I would come back to the space, and he would be like, “Oh, yeah, I just talked to Tom, and he loves the name!” And then it was “So-and-so, she loves the name!” [laughs]. And the next one, and one by one …

Kahan: You have to admit, we asked people anonymously: Here’s a list, pick a name. And it got down to two names.

Seitan: People picked it more than any other name, for sure.

Madia: Actually, it’s brilliant. It’s a total contrast, if you see the name, hear the name, and then you pull up and see this fishbowl of a white interior. It’s brilliant. It’s absolutely brilliant.

Kahan: For most people, you hear the name, and it conjures up something warm and fuzzy. My mom’s era thinks of the song “Bye, Bye, Blackbird.” For people a little later, they think of the Beatles song. You don’t think of a stark, sleek restaurant, and that juxtaposition rustles up your expectations.

With construction moving along and a name finalized, the only missing piece was the money needed to finish.

Madia: So we had the space, the business plan was written. We had direction; we just needed more money. So again, here we go on a quest for money. My mom is getting radiation treatments—18 or 20 treatments. I took her for the treatments every day, after going to work the night before, then would go back to work. She gave me one more chunk of money, $50,000. Paul talked to his family. Eddie got his dad convinced. Ricky's piling up on credit card debt. And we all sat down one day—we met almost every day—and we were almost there.

Seitan: I had my money saved up, and $30,000 from my parents, which was all their savings from the previous four years. That was it. I showed my dad the place where he was going to put all his money, and he looked at me like I was out of my mind, but he was like, “You know, I'll probably never see this money again, but here you go. You know, whatever, if you need it, it’s yours, unconditionally.”

Diarmit: That's what everyone said.

Renee Johnson: I knew that Ricky was doing this restaurant thing, and I really wasn’t paying too much attention to Ricky, because in those days I’m having babies, you know. My mother was really into it, but I just thought it was some kind of phase, so I ignored it. My mom didn’t drive, so I’d take her down [to the space] so she could look at it and I’d go in and look around, okay, fine. I’d look at the blueprints like I really knew what I was doing. I had no idea.

So I did see basically what he was doing, and I would find out through my mother that he was maxing his credit cards out, and he was selling his car and trying to come up with all this money for this restaurant. So I think it was a phone call or something, he calls me up, and I said, “Well, how’s it going?” He goes, “Well, I’m not doing too good.” And I go, “What do you mean?” He goes, “We’re short.” “Well, what does short mean, Rick?” And he goes, “I need money.” And I said, “What kind of money you talking about?” He goes, “Well, I need $10,000.”

And I went, “Yeah, okay. So when you want it by?” And he was like, “What do you mean?” And I said, “I’ll give it to you.” He said, “That’s it, no questions asked?” I said, “You’re my brother.” I was a waitress and I don’t even know why I had money, but we had money put away. I think it was like a Monday or whatever when he called. I was waitressing at Noodles, and he came in for Tuesday night prime rib with Donnie. They sat in a booth, and I gave him the money. And if my memory serves me correctly, I think I picked up the bill for dinner, too. But that was how that went. It’s your brother. It’s your family; they ask for help, and you just do it, that’s it. Period.

Madia: Besides the consulting work, Eddie's working two jobs. And Ricky's still working at Club Lucky, bartending. So we're still working our jobs, and we're still trying to build this space and there's no money.

Kahan: I had spent time working for a couple of different people, one of whom had this giant storage space with tons of restaurant equipment in it. I insisted that he pay me in cash, because he had a kind of sordid reputation. I asked for cash and the equipment. Every time when it was payday, he would let me go in the room and take 30 nine pans or something, and he'd give me an envelope with cash in it. One day, I rode home on my bike with a heavy, huge pasta machine in my bag. Once we started the project, I started buying cookware with my own money and stockpiling it at home. We still have 98 percent of that cookware at the restaurant.

The space during construction after the landlord put it up for sale.

Johnson: They were maybe three months, six months into work on the space when Dion sold the building, while they were still in construction. They could have bought that building for $250,000 back then, but they didn’t have the money. I didn’t know that at the time—if Ricky would have come to me, I could have bought that building for them.

Kahan: We would drive around in the city running errands, and the whole time we'd be like, “Where do we get more money? We need more money; we're not going to make it. We're way short.” Just stressing out, unbelievably. And Donnie and Thomas [Schlesser] had some giant battles, because we didn’t know what value engineering was. We didn't know what anything was at that point.

Madia: We really didn’t know what that space was going to look like before the drywall. The suspended ceiling, any of it. This is Thomas’s sensibility; it’s fucking brilliant. When you stand back, and you look east from the west side, he gave you a frame, actually framing a sculpture, and that sculpture is a hanging piece of material: the banquette. And that’s the piece of art, the sole piece of art for that space. Brilliant. He was bound for stardom. He changed the landscape of restaurant design in Chicago for a long time.

Kahan: The space is, you know, stunning. To see into the front window, it's really elegant, understated and fun.

Diarmit: That was a great feeling. It was a beautiful design; it launched both of our careers. We just had to get it built.

Diarmit, Madia and Kahan meet with staff.

Kahan: None of it would have happened without Ricky. They had all of his tradesmen buddies who helped us out, Ricky and Donnie. They're amazing guys and there's a huge long list of them. It was a combination of super-chill guys who totally knew what they were doing and helped us for nothing, and guys who were horrible who we used because that was all we could afford.

Construction moved along, and the restaurant was almost ready to open in November.

Tom Denney: I met Paul when we were working at Erwin. I left Erwin and got a job cooking at Soul Kitchen. I ran into Paul, and he told me that he was leaving Erwin. He had hooked up with these guys and was going to have his own restaurant.

We met up for coffee at Uncommon Ground, and he told me about the new place. He had the blueprints with him. He was super proud and excited about it, and he sucked me up in the excitement. I was thinking, “Why is this guy talking to me?” Then he said he thought I would be a good sous chef.

Being ignorant to the whole opening process, I thought they would be ready to open in a month, so I gave Soul Kitchen my two-week notice. Then Paul told me they weren’t even done with the building. So I ended up giving the longest notice in line cook history; I stayed there another five months.

Stephanie Samuels: I was friends with [Paul’s then-girlfriend] Mary, and met Paul once they got together. I had introduced Paul to Erwin when he started cooking. I knew Paul was looking for something, and he said he was going to open a restaurant with Donnie.

I remember working with Paul on the dessert menu. I was really, really excited about that apple tart with goat cheese ice cream. I didn’t know what I was doing; I was flying by the seat of my pants.

Denney: They were finishing the restaurant, then, this one guy freaked out, and all construction stopped. Donnie found this other guy, Joe, who showed up with 10 guys on stilts, and within two days all the drywall was up and ready to be painted, while some other guys put in the floors. Suddenly it was ready—this was mid-November. Paul and I started working on the menu, although he had a lot of it worked out. He was in love with Alice Waters and Alfred Portale, their food. Thanksgiving weekend, we had the entire staff in, doing tastings.

Kahan: When I worked for Rick Bayless, we went to do a beer dinner in New York, and I had a meal at JoJo that was super influential for me—incredible. The menu had 10 items—five appetizers, five entrees—but it was huge in size. But everything was incredibly well executed, super tasty, and I really liked that aesthetic.

I think we all had little bits and pieces that we had seen around the country that we wanted to incorporate into our restaurant, and we did. Like when we poured the soups out of copper pots into bowls at the table. It was something that Jean-Georges was doing at JoJo that I thought was really cool, so we ripped it off.

We were fearless in the development of our concept. We were probably too stupid, honestly, to think, “Well, this isn't going to work.” People would tell us, “Oh, Chicagoans won't go for that, it's too this or it's too that.” We didn’t have time to listen to any of that; we just did exactly what we thought would be great.

The endive salad in a potato basket, which has been on the menu since Blackbird opened.

Kahan’s opening menu was composed of American dishes with French influences, and it reflected his focus on seasonality and ingredients. Dishes like his curried corn chowder with apples and lobster, house-made charcuterie plate, Arctic char with littleneck clams and fennel, and endive salad Lyonnaise served in a potato basket quickly became classics.

Kahan: Oh my God, the endive salad. Brutal. It’s still on the menu, unfortunately; I don’t like to keep stuff [on the menu] so long. But people love it. That was just an obsessive thing, I hated just putting the salad on a plate. It needed to be contained. There's a little obsessive-compulsive in it. It's all good. The tuna tartare, that was another early favorite. That flatbread dough we used for the tartare cracker is the same recipe we now use for oyster crackers at The Publican.

Samuels: At that point, the farm-to-table thing wasn’t a catch phrase. I knew he had the palate for it. He wanted to do something that was different.

Johnson: Friends and family were invited over for a soft opening, and I really didn’t want to go because I heard they were going to have French fries that were fried in duck fat, and I didn’t want that stuff. Back then, I made Hamburger Helper. But my mother wanted to go. Okay, fine. I’m going to go, take my mom. I paid for it on a credit card, and I think it cost like $100, or whatever, which to me was a lot of frickin’ money for dinner because I didn’t go out for dinner. And two days later the phone rang at home and it was Ricky on the phone. And he said, “Renee, somebody wants to talk to you.” And I went, “Who?” And he gave the phone over and I hear, “Renee, it’s Donnie.” My heart just skipped, because I thought my credit card was declined. That’s the very first thing I thought, was it didn’t go through. And all he said was “Help me,” in this little voice. And I went, “Excuse me?” He said it again: “Help me.”

He was totally overwhelmed with everything he had going. Donnie was very controlling back then. He wanted to go through every invoice, line by line. He wanted to do everything. But not one person can do it; you can’t do it all; it’s impossible. So I went in to help. He had a big dining room table, and we would switch off at the desk. I did all the invoices. I had them in a milk crate; I didn’t even have a filing cabinet. It got to the point where I was just tired of handwriting them. I even brought in my electric typewriter to type checks.

Kahan: On opening day, the four of us were waiting in the window for our final inspection. This guy comes up and says, “Hey, can I wash the windows?” We were like, “Yeah, no problem.” We sit there, and he washes the window and we pay him. Then after, we look at the window, our new window, and there are scratches in the glass, from the towel. There were circular swirls cut into the glass. Before we even opened, he scratched the windows all to hell. You can still see them there now.

Madia: And you know, we’ve asked people since then how it could have happened, what scratches glass. And they say nothing could put those scratches there.

Former sous chef Tom Denney, Kahan and former server Jason Finn.

Denney: That first night of service, man, it was crazy. Everybody was running around, nobody really knew what they were doing. It was pretty much the front of the house coming back to the kitchen and yelling at us. At some point, I was like, “Fuck this, I’m out of here.” It was probably 9:30 or 9:45, and I threw my tongs down and went to the basement.

Paul came downstairs and was like, “Dude, what the fuck?” I was like, “I don’t know, what the fuck?” He was like, “It’s just the opening night. This is going to be the worst night ever. It’s not going to get worse than this. You just have to do it.” So I went back upstairs to clean up and break down the station. I think I got out of there at two in the morning, and planned to get back at eight in the morning to prep.

A month after opening without a liquor license, they pushed to secure one in time for New Year’s Eve.

Diarmit: I don't remember opening night so much as I remember New Year's Eve. That's the day we got our liquor license.

Johnson: The liquor guy said, “You’ll get your license, don’t worry about it. I’ll have your stuff ready, I’m going to deliver it to you, no problem.” And New Year’s Eve, like at one in the afternoon, they got the okay on the liquor license. It was like a frickin’ bookie joint down there, because everybody’s on the phone calling up this guy for wine and that guy for liquor [laughs]. Oh my God, that was hysterical. But they pulled it off. They had liquor for New Year’s Eve.

Diarmit: It’s the biggest day of the year, and trucks were pulling up in front of the restaurant dropping this kind of booze off and that, and we're just trying to figure out how to make this work for real.

Madia: I remember thinking to myself, “If by the end of the night, I don't have a heart attack, I'm going to make it,” because the fucking tension was unbelievable. Boxes of liquor are rolling in, we had some stuff, didn't have some stuff, wrong vintages, everything.

Seitan: I remember we were frantically typing up the wine list. We didn’t know what we had, what we didn’t. It was nuts.

Former pastry chef Sheira Harris with Diarmit in the space during construction.

Denney: We decided to do a special scaled-down menu for New Year’s Eve; we just wanted to get through the night. But we still got really hammered in the kitchen, in terms of numbers. I remember the snow that night; there was an awful storm. We got out at 2 or 2:30 in the morning. Kelly [a line cook], Sheira [Harris, the first pastry chef] and two of the dishwashers were left, and I was supposed to drive everyone home, but my car is stuck in a snowdrift. Ricky is like, “Hey, here are the keys to my car, just bring it back in good shape and put in some gas.” It was this huge fucking boat, like a Lincoln Continental. Then Ricky says, “Just to let you know, be a little careful, the steering wheel is a little loose.” The entire ride home, the steering wheel would turn 45 degrees before the wheels would turn. And the roads were covered with snow. We were like, in a flash, half the Blackbird kitchen staff could be gone.

Kahan: We had no idea how it would go in the beginning. You know, I think one of my best qualities is that I don't think about how things will be six months ahead, I think about tomorrow. And so I never really thought ahead. It's just like, every day you do the best you can, just come in, turn the screws, try to make it better.

Madia: It was break-out time for us for Chicago, and I think this little restaurant was the antithesis to the others. The independent was gaining a voice instead of the big guys.

We feel our success comes from our collaboration. We love the fact that no one person is bigger than the whole. We argue a lot. We argue a ton … maybe once in a while. But at the end of the day, we know that we’re not the important factor. It’s our staff, it’s our guests. It’s Ricky’s sister and mom and my aunt Rita, helping out. It’s Paul’s dad bringing over corned beef sandwiches. It’s Eduard’s father taking a chance and giving us $30,000 for us to finish this project. It’s my mother, who passed two months before opening. She never got to see it happen. Next

Blackbird Chapters

- Log in or register to post comments