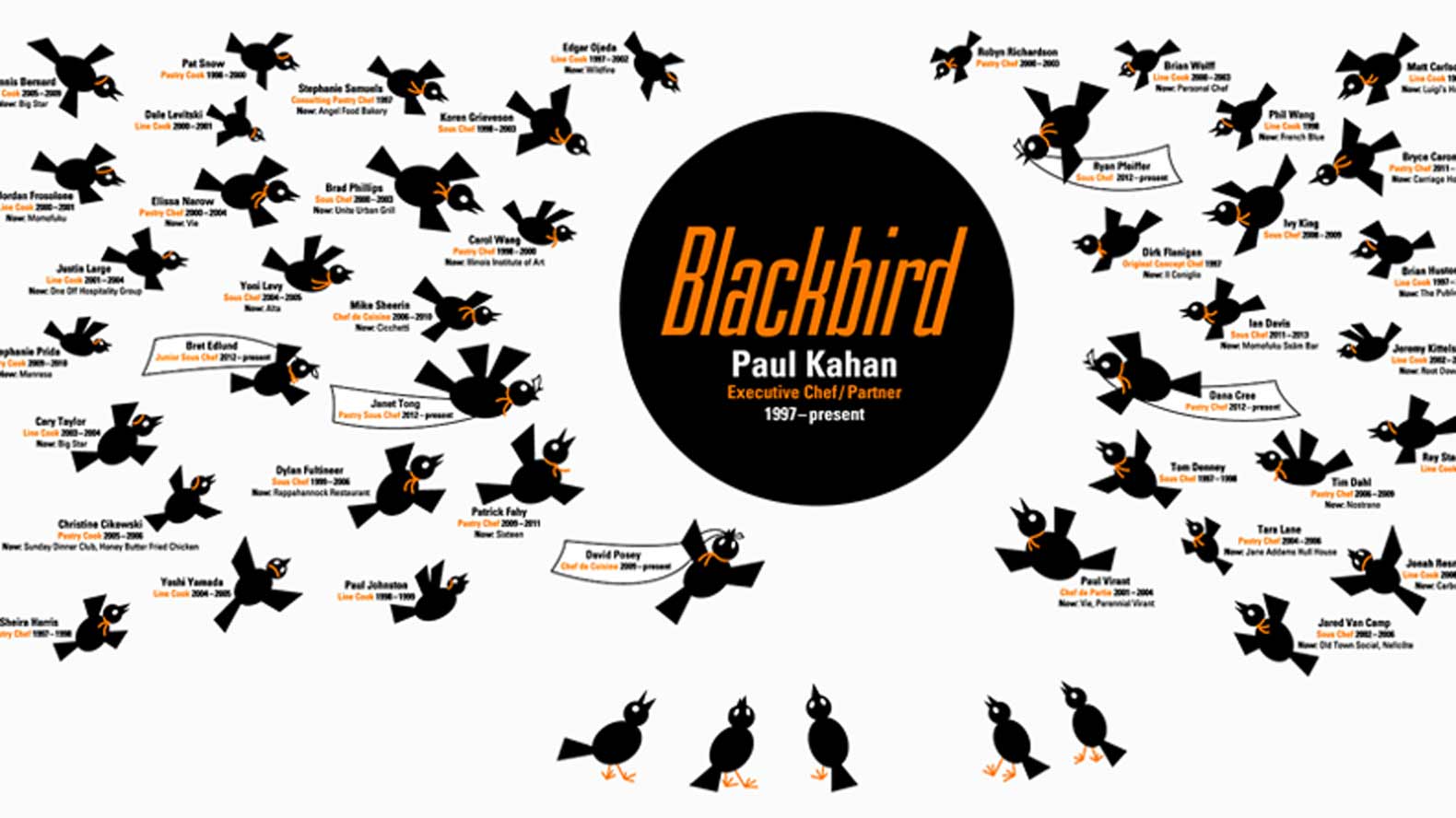

Chefs and Restaurants

Project Blackbird: The First Year

Blackbird opened December 1, 1997, and got a liquor license on New Year’s Eve of that year. Going into 1998, they hoped for business to pick up during what is traditionally the slowest time of the year. The food was a draw for many, and the design received accolades mixed with a few complaints about the tight seating.

Madia: I remember Sheira Harris [the first pastry chef] called me over during service and said, “My friend is an architect, I'll introduce him to you later, but he noticed that the banquette is uneven.” And I was like, “Really?” So I stood there, and I looked at it, and then I thought this guy's out of his fucking mind. I’m in this space every day, and I’ve seen 1,000 different iterations of it. On top of that, there were the fights, the battles—everything it took to get the place built, so you take any criticism so personally. It hurts; it stabs you. I'm sure Eddie felt the same way being scrutinized about the floor, or Ricky with the wine and spirit list or Paul with the food.

Diarmit: We saw [restaurateur] Jerry Kleiner basically on his knees on the sidewalk staring into the restaurant to see how we kept the banquette up on the wall. He was like, “How's this happening?”

Madia: Business was poky at that point, but it eventually started picking up. We were making our way. I think word-of-mouth played the most important role; it contributed to a lot of our success. Gary Weidner, an artist, was a big component of getting people to gather at the restaurant on Thursday, Friday and Saturday nights around 10 p.m. That would be their first round of drinks before they went out for the evening. So I credit a lot to Gary for bringing in a lot of business. He traveled in a circle of people who wanted to see and be seen.

Kahan: I think it was the space that brought people in, I think it was everything. A lot of the servers we had were incredible. From the beginning, we wanted to make people happy; it was sort of a prime directive. We were like, one for all, all for one. If I had to bus a table, I did it. We were all going to help everywhere. We wanted to make sure people had a great experience.

Phil Vettel: When I first went into the restaurant, it was off-putting. It was smaller than I would have liked, more austere and noisier than I would have liked for what I thought they were trying to accomplish food-wise. Then I ate the food, and well, I would put up with a lot more just to eat Paul’s food.

Kahan: We’ve looked at the seating details a million times. A million times. Seriously. I won’t lie, I’ve sat and had meals there, and been like, “This is fucking uncomfortable. I hate it.” But then you go back and see what you can fix, how you can change it.

Madia: We compensated by pulling chairs out, making a giant effort to pull tables out. Step back. Let the guests go in front of you. And micromanage that banquette like no one’s business. We were super conscious of the guest, always.

Diarmit: This was a time when sport coats were required at a lot of your upscale restaurants like La Strada on Michigan Avenue or at Charlie Trotter's. We never had that philosophy. Everyone was welcome. If you came in wearing a baseball cap, gym shoes and shorts, you were going to be very uncomfortable, but we'll serve you. That was our philosophy from the beginning.

Kahan: The wine list, the food, the way that we welcome guests; we were casual enough that you could come here just to relax and have a drink at the bar.

Blackbird’s menu attracted local chefs early on, and it stood out by offering an amuse course to guests and finishing the meal with mignardise—elements that were limited strictly to fine dining establishments until then. Kahan presented his take on New American cooking with a French influence, showcasing quality, locally sourced, seasonal ingredients, which was unusual at the time.

Kahan: I had been to France, and that was the first time I was ever exposed to an amuse-bouche. I thought, this is cool, and I think it would be great in a more casual restaurant. Just to make people feel like, “Man, I'm getting all this free shit. I didn’t order this, I'm not paying for this.” An amuse course is fairly common now, but I still think it's really nice. It's a gift and it sets the tone.

Vettel: I was certainly happy with it. At that time, if you were going to get a little gift from the kitchen, it was in a more formal setting. The amuse was a nice little way of setting it apart.

Samuels: Paul was really interested in doing mignardise. Every year at Christmas I made candies to give people: goat milk caramel, ginger caramel, some nougats, other candies. I remember Paul talking to me about the caramels, about giving some to guests after dinner.

The opening menu from December 1, 1997.

Minami: I remember thinking the menu was way too ambitious. Every single thing was so involved. When you’re working in a kitchen, you want a couple of things at your station that are easy. I remember thinking, “I don’t know how he’s going to do this.” Stephanie [Samuels] and I would get together on Sunday nights and talk about Blackbird—Paul was like our little brother. But that’s probably what created the buzz; the specialness of every dish was really surprising, especially because it was all happening at this small restaurant where no one really knew the chef.

Kahan: Pretty much right off the bat, we had chefs coming in to check the place out. I remember John Hogan came in with Patrick Concannon and three other guys. He was one of the first chefs who I recognized, and over the years, he’s been a mentor who I totally respect. He's an amazing chef who doesn't get credit for how talented he is. I remember he ordered the guinea hen, and he enjoyed his meal, I think. Guys like that spread the word.

Charlie Trotter came in during the first six months with a group, and it was terrifying. Of course, everyone said hi to the table, and he stood up and he stood like two inches from my face, and I was thinking, “What the fuck is wrong with this guy?” You know? Step back.

Diarmit: I didn't know who he was until afterwards, and I thought the same thing when I was waiting on him at the bar.

Heather Medina: I waited on Charlie Trotter both times he came in for lunch. I remember Paul being like, “Don’t give him a menu – we’ll send him food.” I just thought, Oh God; I hope he doesn’t ask me about wine. Donnie with his fashion sense, said, “I know you got that at Salvation Army, but you are so Calvin Klein right now. I love that you are wearing those glasses while waiting on Charlie Trotter.” Sheira was red-faced, just trembling.

Kahan: Sheira used to work for him, and she was like, “The chef's here, the chef's here! Oh my God!” But Trotter did a lot for us. He used to bring chefs in from around the world, and I was very respectful of him. The opportunity to bring a chef from France or Switzerland or anywhere, into a place that was serving really good food but was casual, refined and comfortable was an exciting thing.

Chocolate crêpes with espresso mascarpone and hazelnut brittle was one of the most popular desserts for the first few years Blackbird was open.

Denney: One Monday night, we did 18 covers, and Mindy Segal, who was working at Marche as a pastry chef, walked in late with a friend and sat at the bar. Paul knew her, and he went up to her and her friend and asked her what she wanted. She said, “Why don’t you do something different?” Like, “Dazzle me.” I was like, “You’re going to walk in here at 9:45 and you want us to do a tasting menu?” But Paul was just doing whatever he needed to do to impress people in the industry.

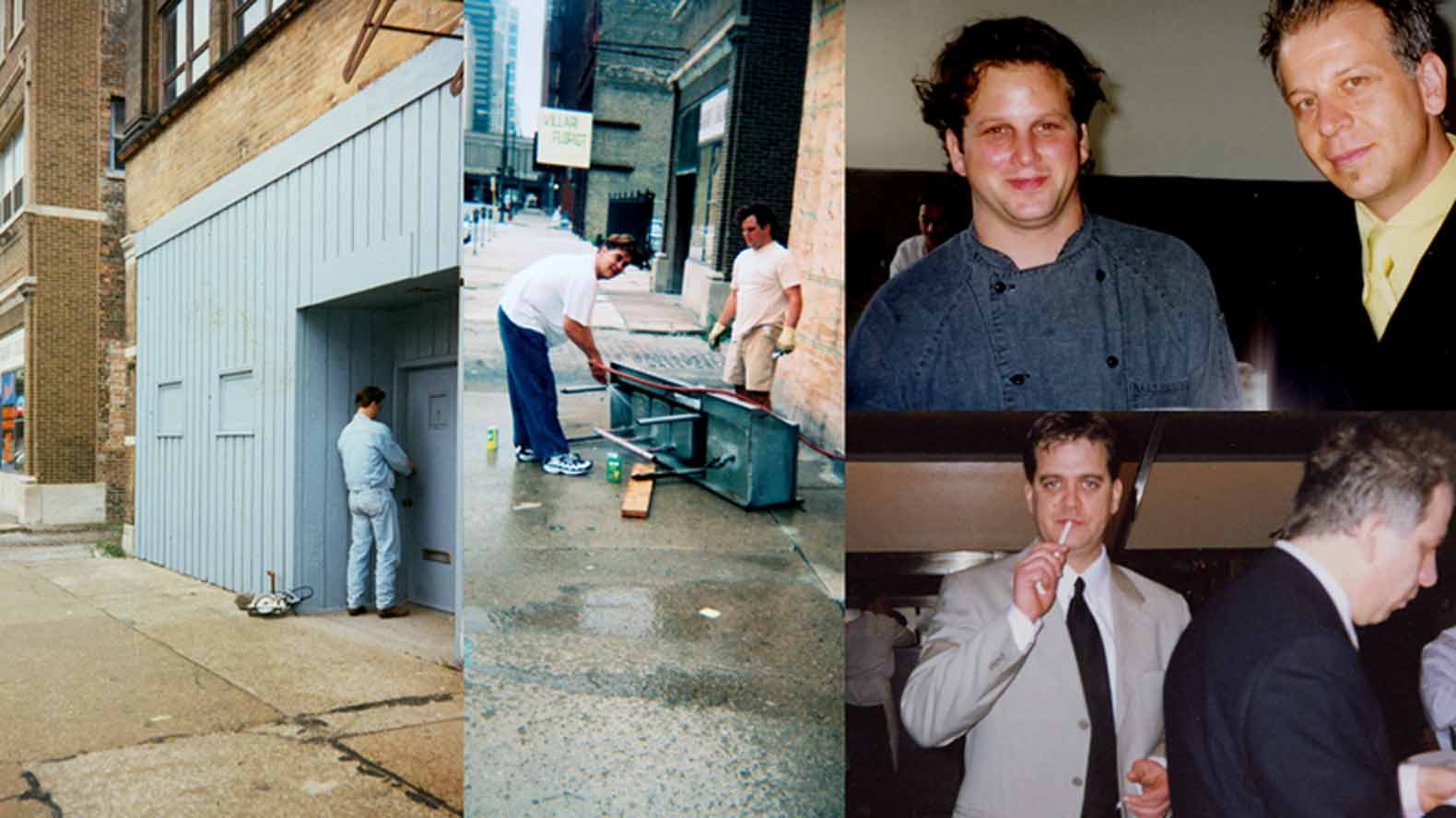

The staff at Blackbird included alums from Erwin, Club Lucky and other restaurants the partners had worked at before opening the restaurant.

Kahan: We mostly hired friends and acquaintances. Jose Sibre [a line cook] worked a station that required two people by himself. He worked alone with a dull, serrated knife; he cut everything with it.

Denney: The magician! Paul and I used to say that if we had 10 Jose Sibres, we could take over the world.

Phil Wang: Those potato baskets for the endive salad were the bane of my existence. All of a sudden, Jose Sibre came in and made a hundred of them like it was nothing.

Paul Johnston: I was working at Okno, and [former server] Loman was working at Blackbird, and he said I should go down to Blackbird and talk to them. So I went in, staged for a day, hung out on the line, worked with Matty Carlson [former line cook]. It was countdown to kickoff, and I started going through his mise en place, which was messed up, so I think that helped me get the job. Paul offered me a full-time position that night.

I thought the restaurant was really chef-driven. The Blackbird guys really seemed to have their shit together. Paul gave me some books to read, a great bottle of Normandy cider to try. I had never seen that before. He had a great passion for wine, too, and I was just getting into wine. It felt different, like more than a job. I liked being there. I would get there at 10 in the morning, and work to close.

Diarmit’s mother, Pat Snow, and former line cook Paul Johnston.

Johnson: I don’t even remember how Mom [Pat Snow] was called in to help. She’s always been a baker and she wanted to learn, so she just wanted to be somewhere at the side and help. She did that for years. She would come in, roll [chocolate] truffles in the basement, take care of everyone.

Pat Snow: I wanted to help, and Renee was going in every day, so I could go with her. They would leave me notes: “We’re making ice cream today, so I need you to separate 60 eggs.” And then I got mad that they were throwing out the whites. Sheira was great, but she was wasteful. I rolled the truffles. I remember I did a tray of truffles, and someone spilled a little water on them. And she was so mad; she tossed out the entire tray. I looked at her, and normally I am so peaceful, but I said, “Sheira, you can do that, but next time you do it, don’t do it in front of me.” That was so much work! I fell once while carrying the truffles, coming out of the walk-in, and the only thing I cared about was how many I could save before they hit the floor.

Johnson: Mom would make this huge thing of egg salad and bring in two loaves of bread so everyone could eat. Aunt Rita was Donnie’s mom’s sister and she would come down and help shuck the peas. She was a sweetheart. It was home, that’s what it was. During the winter, it’d be so cold [downstairs], I’d bring a Crock-Pot down and I’d make chicken soup, and I’d pull it outside the office, and that would be the staff meal. We were family.

Denney: It wasn’t too long after Blackbird opened when a trend started of small restaurants doing really good food. I remember feeling proud we were the Blackbird crew; it felt good to say I worked there. There weren’t a lot of people who knew about it, but I remember feeling that people were going to know this place. That was what motivated me to be there for 80 hours a week or more.

Edgar Ojeda: Paul always gave you the freedom to do whatever you wanted to increase your experience. You could work with different products. We were always changing the menu and specials. He was always bringing in new products that I hadn’t seen before. We had a great time there. He gave us a lot of opportunities to show him what we knew, the chance to make dishes for him. That was the good thing about working for him.

A few months after the opening, a fight broke out in the restaurant—one that ultimately changed the direction Blackbird would take.

Diarmit: We were talking about turning the upstairs into an after-hours lounge or nightclub.

Madia: One night, these guys that I was associated with while growing up came in, and they thought Blackbird was more of a social scene than a restaurant. It was five guys, and I remember their bar tab was like, $300. They were drinking wine.

Diarmit: They walked over to tables 32 and 31 and started addressing these young ladies sitting there having dinner.

You had Ricky’s mom and sister working there, Donnie’s aunt that family aspect blew me away.

Madia: We couldn't run food out to tables because they were standing in the way, holding their wine glasses. Paul said, “What are we going to do with these guys?” So I went over to talk to them, because they came from my knucklehead crew. I went up to one of the guys; he’s a boxer, a heavyweight guy. I said to him as politely as I could, “I just wanted to touch base with you. You know, we're trying to get food out. It's an open kitchen and it's a little difficult, so if you wouldn't mind the gentlemen taking their seats. I’m sure the ladies would like to enjoy their dinner.” And he goes, “Who the fuck do you think you are?” I think he was a little bigger than Ricky, and he goes, “The fucking problem with you—you're starting to believe your own press.”

Diarmit: He said something like, “Don't forget where you came from.”

Madia: Yeah, so I pulled back. We all gathered by the computer and I said, “What do you want to do with these guys? Let's just pick up the check and ask them to leave.” That was a mistake. One of the guys was one of my good friends, so I said, “You know what? I apologize, but I’ve got your check tonight and I'm going to have to ask you guys to leave.” And those guys went fucking nuts.

Diarmit: It all transpired when we actually got them out the door. It wasn't much of a fight; it was mostly verbal. Just a couple of punches thrown. Unfortunately, there were diners around to see it.

Madia: I remember the paddy wagon pulled up and the two officers didn't get out of the vehicle. There was some scuffling, and there was definitely vulgarity. I think for the most part everyone was eyeing each other.

Diarmit: We were like, “Is this going to happen or not?”

Kahan: There was some talk of a gun, or somebody said they're going to come back and put a bullet up your ass or something. Donnie and I were in the street, just freaked out.

Braised pork belly with fresh shell bean ragoût.

Madia: I think somebody said, “I'll be back. We're going to take care of this later.” And that's when I said, “Oh yeah? You want me to call your mom?” Because I knew his mom.

Diarmit: And didn't you see that guy very shortly after—like a week or two after that? I think it was shortly after that we made a visit to him and things seemed to be okay.

Seitan: We never got out of the car, but he came over to the car. I can't remember the conversation exactly, but everything seemed to be fine.

Madia: After that night, we made a decision to stand our ground and keep it a restaurant. No DJs, no spinning, no fucking around. That was definitely the defining moment for us.

Blackbird’s popularity increased, and it became a dining destination.

Matt Carlson: The fame Blackbird had in the first six to nine months was crazy. Every day it got busier and busier. Every weekend became more intense. It never stopped. From doing one and a half turns to three and a half turns a night. I remember when Rick Bayless came in, Paul was nervous but he was totally impressed. Cindy Crawford came in. Lenny Kravitz loved the lobster corn chowder. The guy from Sonic Youth. Michael Jordan, that was cool. The whole Wirtz family. It was definitely the be-seen place.

Wang: We were having so much fun. There were definitely some funny moments where I walked away with egg on my face because Paul cooked me under the table. I enjoyed that. I really learned a lot from him.

Brian Huston: I think I was their first hire after the opening crew. It was about three months after the restaurant opened, and I had just finished working at Zuni Café in San Francisco. I had worked at Spiaggia before that, and was thinking about moving to New York. I talked to my former sous chef at Spiaggia, Tim Coonan, who now owns Big Shoulders Coffee. I asked him where he’d had his last great meal in Chicago, and he said to try this new place, Blackbird.

I remembered Paul a little from back when I worked at Heaven on Seven, from working the charity circuit; his crazy hair and raccoon eyes. So I went in and tried out, and then I knew I wanted to work there. I wrote Paul a letter, following up with a phone call, then a thank you note after the interview. You don’t see that now. I stuck out in that I was persistent and grateful.

Blackbird was the first young restaurant I had worked in. All the other places I had worked in were established. They had been open 10 years and I was cook number 120. But you had Ricky’s mom and sister working there, Donnie’s aunt; that family aspect blew me away.

It was a fun summer in Chicago; the Cubs were winning, I loved it. I had a good time. I was single, going out a lot. Paul had to sit me down more than once to say, “You are having too much fun, you have to take this more seriously.” We listened to music and the Cubs and made great food. I was the roundsman, so I worked every station. Back then there was Jose Sibre, who did the job of three people. Koren Grieveson [former sous chef] was the quiet one, but she definitely had skills.

He was just doing cooking at a level that few people were attempting.

Wang: I remember why I left Blackbird like it was yesterday. It was a Saturday morning, and I was in my apartment getting ready for work. My girlfriend answered the phone, walked in the bedroom, and her face was white. I thought someone had died. She said, “Daniel Boulud is on the phone for you.” Traci Des Jardins had sent him my name, and he was opening the new Daniel location in the old Le Cirque space. He says to me, “I have a job for you on the opening crew. Can you start tomorrow?” I said, “I live in Chicago, I can’t be there tomorrow.” He said, “You have one week.” So eight days later, I was sleeping on a stranger’s floor in New York. Blackbird was amazing and I loved working there, but it didn’t have the reputation that it has now. I loved the food and Paul, but Daniel was a huge opportunity.

In the summer of 1998, Blackbird was awarded three stars by Phil Vettel of the Chicago Tribune, who complained about the cramped quarters but lauded Kahan for his food. The already busy restaurant became one of the toughest reservations to get in town.

More austere and noisier than I would have liked… Then I ate the food.

Vettel: I was pleasantly surprised by the food and how intelligently it was put together. Every dish had something really memorable to it. He was just doing cooking at a level that few people were attempting. It seemed by the menu descriptions they weren’t suffering from a “Look, Mom, I’m cooking” need to show off; there was a certain modesty to the operation. They let the food speak for itself.

Huston: Blackbird was a hot place. You felt like you were part of something that felt pretty special. The awards and accolades will help cooks stick around. It’s flattering. It’s street cred—you’re respected by other cooks, other chefs. People came in and had amazing meals. And it was an independent restaurant. It felt like the team was doing it, making it work. I was kind of a punk kid that thought we could always be doing better, but didn’t know how.

Denney: Every Saturday was the same. I was always so paranoid about how service would go, but I felt like I was missing out on being in touch with what everyone else was doing in the kitchen. I was sous chef, and I needed to know how the other stations worked. At some point, about six months into it, I felt like I had given my life to the place, and I hadn’t been given what I needed [to succeed in] that position. I think Paul picked up on it. We hired Tall Paul [Paul Johnston], so we could have someone who could come in and work the grill and I could focus on being sous chef. After that, I didn’t work dinner service, except Saturday night. That lasted all the way to winter. By then, I was getting really burned out.

My wife said, “I’ve had enough of this. You’re working 80 hours a week for not much money, and this isn’t letting up. Make a choice, me or Blackbird.” So, I was ready to go. I don’t know if Paul knew I was interviewing, but it seemed like Koren was there really quickly, and was ready to take over. It felt a little bit harsh; my last night was a typical Saturday night, nothing like, “It’s Tom’s last night, we’re going for drinks,” or anything.

There are different times in my life when I regret leaving. I don’t think there were hard feelings. Of all the people I worked for in this industry, Paul was my mentor. He’s the person I credit with teaching me a lot about managing kitchen staff, about food. I feel very proud to say I was the opening sous chef at Blackbird. Next

Blackbird was a hot place. You felt like you were part of something that felt pretty special.

Blackbird Chapters

- Log in or register to post comments