Chefs and Restaurants

Project Blackbird: Partners

These days, it’s nothing new to go into a restaurant and order fine dining-quality food sourced directly from local farms and served in a stylish-but-casual atmosphere. But it wasn’t that long ago that the phrase “farm-to-table” had yet to be uttered – let alone overused. Menus weren’t covered with farm references, and the majority of restaurants were either white tablecloth fine dining destinations or strictly casual.

If you look back to the 1990s, the landmark, game-changing restaurants were found on the coasts – think Campanile in Los Angeles or Vong in New York. At that time in Chicago, the spotlight was on fine dining temples of French cuisine like Everest, Charlie Trotter’s or Ambria, where jackets (if not suits) were required, and you were expected to keep your elbows off the table, keep your voice down and remember how lucky you were to be there. Restaurateur Richard Melman filled the city with his high-concept Lettuce Entertain You restaurants, and diners flocked to Hat Dance, Scoozi and Papagus for giant portions of largely American takes on Mexican, Italian and Greek food, respectively, served with flair. A few pioneers were establishing the West Loop restaurant district, with spots like Marche and Red Light that were as focused on the concept and theatrics as on the food.

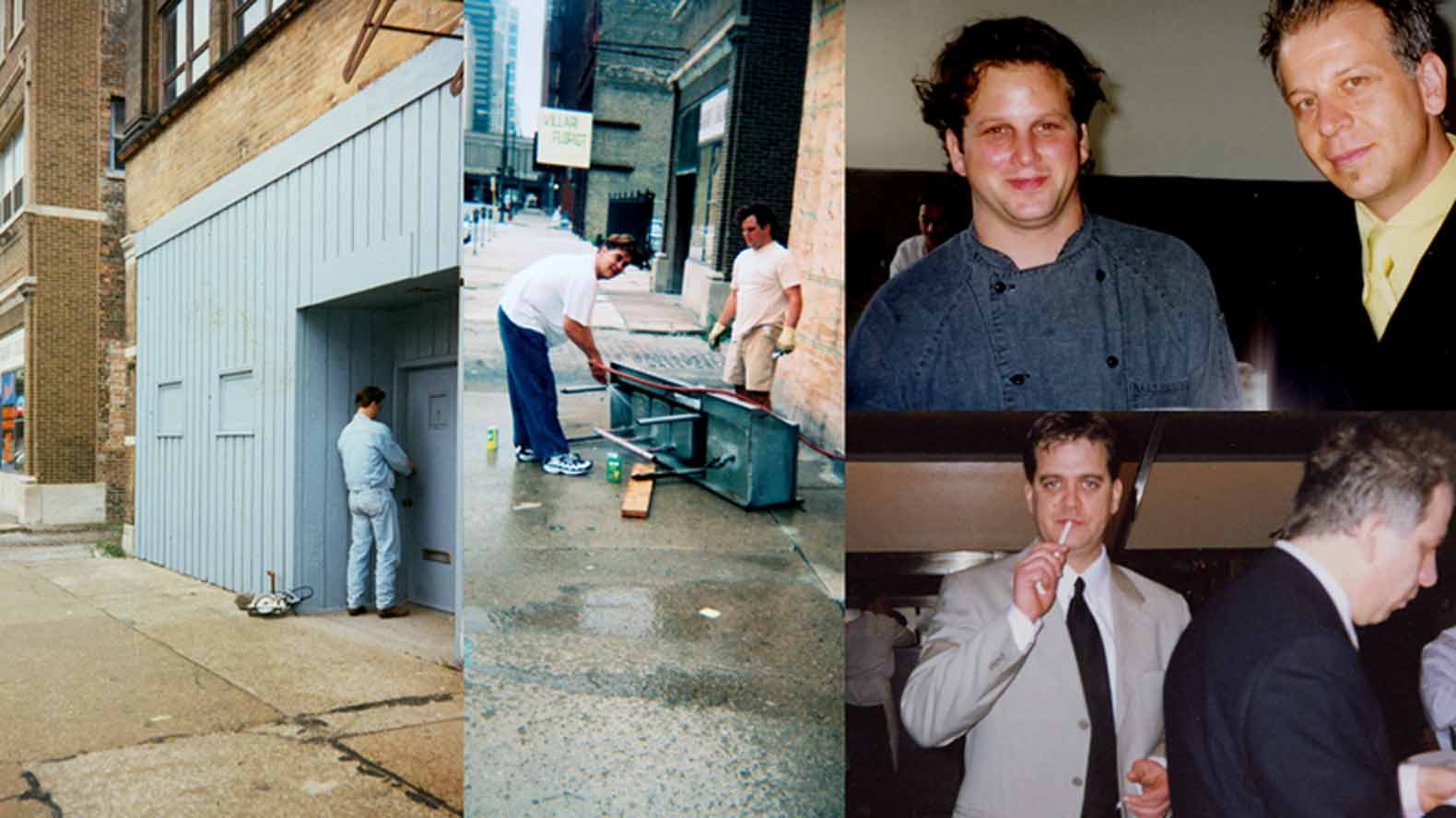

Then, on December 1, 1997, an unlikely group of men opened the doors to their first restaurant, Blackbird. Not many people would have guessed that they would be successful. They didn’t have a lot going for them, to say the least. They begged and borrowed money from family members to open the restaurant. They struggled to renovate the debris-filled space their landlord leased them, still splattered with the markings from his paint-ball games, then scrambled to hang on to the space when he put the building up for sale just months later. A series of contractors and workers went through the space, few reliable or able to understand the blueprints. And the money kept running out.

Somehow they got it open, and in the 16 years since, Blackbird has changed the American dining scene. The restaurant put chefs on notice that fine dining-level food could be served to people in jeans and sweaters. That New York-style seating – so close you’d better be in the mood to hear about your neighbor’s divorce – would actually play in a town far more used to roomy chairs accommodating equally roomy Midwestern bodies.

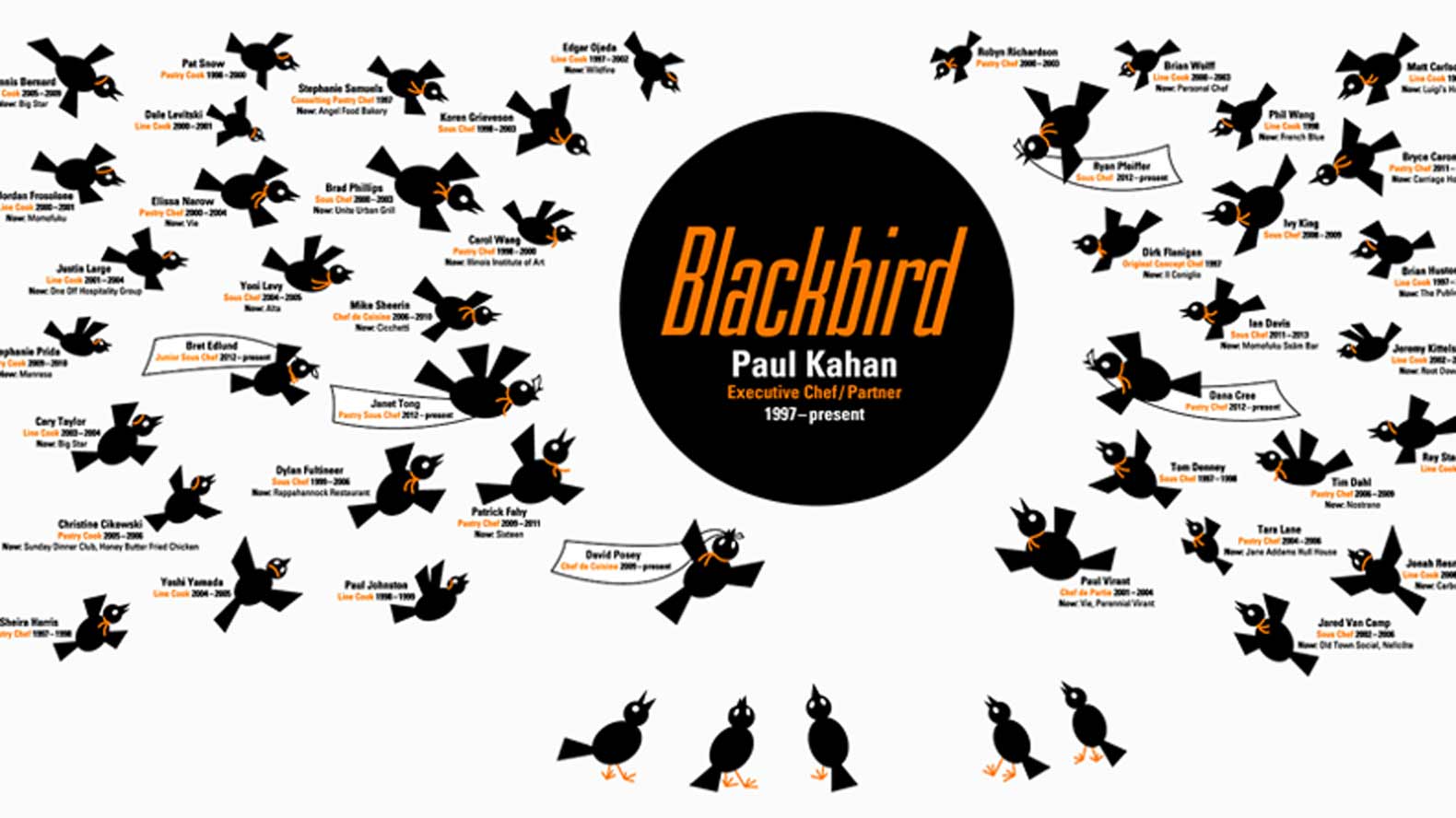

You don’t have to have eaten at Blackbird, or even in Chicago, to experience its influence. Many of the dozens of chefs who have worked there over the years and gone on to other restaurants around the country cite their time at Blackbird as the most influential on their career. Since opening, Blackbird’s success launched one of the most exciting restaurant groups in the country. Here’s how it happened:

In 1996, Donnie Madia and Rick Diarmit began talking seriously about opening a restaurant together, called Table. They tapped Dirk Flanigan, a local chef, to partner with them, and set out to find a space.

Donnie Madia: Ricky and I worked together at Alexander's, under Dmitri Alexander. We wanted to do something together, so we set our sights on finding the space in the West Loop, because we felt that that neighborhood was up and coming. It already had some restaurants; Vivo was there, Palladino was there, Marche. [Restaurateur Jerry Kleiner] was on fire, he had three stores on Randolph, so we looked there. We took measurements in the Sushi Wabi space, and we also looked at the De Cero space with Dirk Flanigan.

Dirk Flanigan: Back then, I had two things going. I was still a singer in bands: 77 Luscious Babes, Pig Face. And I was cooking. I remember Donnie approached me. He was like, “We are going to open this restaurant.” I think he was going to call it Menu. It was very cool, a lot of R&D going on. We would go out to dinner, then smoke a hundred cigarettes and drink whiskey and talk about it. We were setting out to make something different. Donnie had design ideas on paper, we were looking at spaces with Ricky. We looked at a space with these crazy basements and sub-basements. He had this idea about sunken areas for seating.

We didn't have any money. We had nothing. Zero.

Madia: There were two Greek families that owned all that property in the first two blocks on the north side of the street, and someone else owned everything on the south side of the street. So we're learning all this and we're trying to negotiate a lease. We signed two letters of intent, but walked away twice. Through Ricky’s connections, we knew Dion Antic, who had a space on Randolph. Ricky and I sat down at my apartment on Grand Avenue and we'd just do small pro formas [calculations], handwritten, on the back table in the kitchen. So we met with Dion and we negotiated the lease and signed the letter of intent. We didn't have any money. We had nothing. Zero. My mom was diagnosed with emphysema. She put $50,000 in a CD and let me borrow $50,000 from her, and then we were on our way.

The Blackbird space under construction.

Rick Diarmit: We put in checks of $5,000 apiece. We signed a lease in September of '96, and we went along, periodically giving more cash.

Madia: I was acquainted with the architect Thomas Schlesser; he designed Vinyl and KaBoom. Thomas' idea, because the space was so small, was to create an oval-shaped table in the middle and no two tops, and then as guests came in, they would fill the table up communally and you would sit next to each other. And that’s what we were going to call it, Table. It was an interesting concept.

Diarmit: Thomas wanted to do a space that he had full control over. I mean, we basically told him anything goes if he'll do it for no charge, so we came to terms with how he came aboard. He had free rein, so we didn't have a lot to say about it.

Madia: I saw something special in Thomas. Did I know how special his design would be? No. I think we took a shot with him and he took a shot with us.

Diarmit: We were fighting for storage space. We were fighting for everything. I remember we bought a fan and a hood, and hung on to them for two years.

Madia: I stored that hood in my backyard. My uncle left my cousin Lewis a truck, and we shoved this 14-foot hood in this little truck. The thing was sticking out about eight feet in the back and we're driving [to the space] and we barely made it before the car died. I dumped the poor truck on Grand and Ogden at a transmission place and the guy called me, and he goes, "Yeah, you're going to need a transmission and engine work," and I said, "Uh, can I just leave it there?" and I just left the poor truck there and it got towed away [laughs].

Flanigan: I was trying to scrape by until we opened. I needed health insurance, and I asked for some ridiculous salary back then for a chef. It was like $40K. At the time, that would have been the most money I had ever made. I had a family and was trying to be responsible, for a 24-year-old. Donnie was leveraging everything—his house, his mother’s house.

Madia: We sat down with Dirk and he goes, “Okay, so I need health insurance for my daughter and I'm thinking about salary. Is there a way I can get paid through the construction phase?” I looked at Ricky and I said, “We can't pay this.”

Diarmit: There was no way. It was impossible. We had nothing.

Madia and Diarmit heard about a young chef named Paul Kahan who was looking to open a restaurant, and they arranged to meet him.

Paul Kahan: I love the real practical reason why I came into the picture. Because Dirk wouldn't work for nothing [laughs].

Madia: You know, when you're trying to do something, whatever business you're trying to do, you talk about it a lot. I would talk about the project with Jill Rosenthal, who was the chef at Ooh La La, where I worked. I like to say that Jill whispered in my ear that her husband worked with this chef over at Erwin’s, and he was looking to get out and open his own place.

Erwin Drechsler was Kahan’s first chef and mentor.

Kahan: I started out working for Erwin Drechsler at Metropolis Café. I had no experience. I had left computer science and was working for my dad as a delivery truck driver. I met my wife, Mary, and started to explore what I thought I wanted to do with my life and got introduced to Erwin. I had an interview and he just basically said, “What do you want to do?” and I said, “I think I want to cook,” and he asked me questions about me as a person and away we went. Erwin was very frugal with products, although very ingredient-driven and frequently at the farmers market. He was the guy who started taking me to farmers markets before anyone else was going.

Ken Minami: I met Paul at the Metropolis Café. I was the sous chef, he came in as an entry-level cook. One thing I always remember about Paul is that he was very serious from the beginning. He would carry a notebook with him and was always writing things down, always thinking about it. He pumped anybody who was a cook for information, writing down recipes. He had a sense of humor, but he was very, very serious about food. I knew something was going to happen with him.

Kahan: We opened Metropolis 1800, and it was a really big kitchen. I was just a cook and, you know, I just didn’t feel like I was getting what I needed to learn there. So I applied at Frontera. I really wanted to work at a great restaurant. At the time, I think [Frontera] was the epitome of independent, well-run restaurants. Everything they do is so intelligent, so well thought out. That’s what impressed me, and I learned a ton there. I got to work with a lot of product that was unfamiliar; I got to butcher a whole fish and truss pheasants and roast them on the spit and all kinds of cool shit that I never did before. But ultimately, I didn't want to cook Mexican food.

I went back to working for Erwin and was the co-chef, with my friend Mike. I think I worked at Erwin at the new space for almost three years. I learned a lot about leadership and being a solution guy, not a problem guy. You know what I mean? Instead of being like, “Oh, this dish sucks,” or “This is fucked up,” I learned how to be like, “Hey, I got a great idea how to fix this, how to make it better.”

Mary had just finished her master’s and got a great job. And so we had a talk about how I wanted to do something on my own, and she said she backed me unconditionally and she'd support me for as long as I needed. So I gave my notice. My approach was networking. I did tastings for chef jobs. I did three or four tastings, and got offered every job. But none of them was the job I wanted. I wanted ownership. I wanted to work for myself, as an equal. I was waiting for the right thing. So the whole time I was networking. Every day I had a list of 30 names, and I called 30 people. One day one of the names on the list was Jill Rosenthal. I just said, “Hey, I’m looking, if you know anyone.” You know, I was just putting leads out there.

And I think my line was, “I'll go into business with you guys, but I'm not going to hang out with you.” Which was a stupid line.

Madia: Ricky and I definitely had this game plan in mind that a chef/owner, instead of a chef for hire, would be a really important factor in the success and longevity of the restaurant. I think chefs at that time weren’t what they became as of five or ten years ago. They were seen as a piece of transportation. The restaurateur was seen as [having] more of the idea behind the restaurant. I think creating a team was more important to creating the success of a place, a restaurant, a thing. It was about creating something really special.

Kahan: Donnie came in to brunch with his girlfriend at the time, and I came out, completely covered with food. I was a mess, going to shows, out late. Donnie and I just said a few words to each other and then said, “Let's meet up.” Erwin had gotten me into this thing of having important meetings at Uncommon Ground. So we set up the meeting for me to meet Donnie and Ricky. I remember I got there on my bike. It was snowing. I'm thinking, “What am I getting myself into? Who are these guys?” I'm sitting there having a coffee and I see this yellow '66 Buick Wildcat go by a couple of times looking for parking and the guy behind the wheel, he’s a greaser. His hair is slicked back, he's wearing black wrap-around sunglasses and he has a cigarette hanging out of his mouth. And I'm like, “It better not be this guy.” I see the car go by a couple of times. He parks, covers it, and sure enough it's Ricky, and then I see Donnie park his mother’s Sunbird across the street. And of course, he's wearing an incredible suit. There was a funny juxtaposition between the car and the outfit; it was a little weird. These guys came in and they said, “We signed a lease, we got a location, these are the plans.” The plans were completely hieroglyphics to me. Up to that point, I had never looked at a set of blueprints.

I remember talking with Mary, like pretty much, “I’m taking a giant chance, but I’ve got to do it.” I mean, you don’t get anywhere unless you take a chance. I caught a drumstick once at a show, I'm trying to remember what band it was. Was it Bun E. Carlos, the drummer for Cheap Trick? I don't know, but on the drumstick it said the guy’s name and his line was, “He who cares, wins.” I kept that drumstick for a long time. He who cares, wins. I was in a good place and said, I'll do it. And I think my line was, “I'll go into business with you guys, but I'm not going to hang out with you.” Which was a stupid line.

Flanigan: Donnie came to me with tears in his eyes and said, “We’ve got a guy who is going to be chef. We could have you come on as sous chef.” I was hurt. I thought my life was going in one direction, and I guess, this was it. I said, “I’m not mad right now, but tomorrow I’m going to be super fucking pissed.” It was rough. But I had my family to look out for. I understood it. It was a business decision, and Paul is a fantastic chef and great person. Donnie was at my wedding a few years ago. We’re still friends. He’s one of my guys.

Madia, Diarmit and Kahan began construction and realized they needed another partner. They approached Eduard Seitan, who worked with Diarmit at Club Lucky.

Eduard Seitan: My family and I came to Chicago [from Romania] to visit some friends of my parents in 1992. Three days into being here, the guy we were staying with was working construction, and someone had fallen off a ladder. So he asks me, “Can you help us out for a day?” It was a Friday, and I worked a full day and got paid $50 for a day’s work. That sealed the deal for me [laughs].

Kahan: Hunger for money!

Seitan: When it came time to go back [to Romania] three weeks later, I decided to stay. I started working construction, hurt myself a lot and was dating this Russian girl who got me started working in restaurants. I was hired at maybe a half-dozen restaurants and fired the next day or two days later, because I spoke no English. I kept saying on my resume that I had experience. I got a job at Club Lucky and worked with Ricky for four years. I think what kept me there was Ricky, the way he ran that bar at Club Lucky. Ricky asked me one day if I wanted to get involved [with the new project].

Diarmit: I remembered a big conversation we once had at Club Lucky during work. He was having a bad night, and I'm already talking about doing my own place, and he was like, “Ricky, you must take me with you” [laughs]. I admired Eddie's work ethic at Club Lucky; we worked together for four years. Plus, he was more computer literate than me.

Seitan: I had $40K—all my savings from the previous four years of working at Club Lucky—to invest in the new place.

Diarmit: The one thing that we all had in common was that we were still young men and we didn't have much to lose. This would be our shot. You know, we didn't have children—we had wives and relationships, obviously, but we were able to say, “What could happen if we take a risk?”

Madia: It's interesting: [We had] a bartender, server, kitchen, and front of the house. Paul would cook and be a partner. Eddie would be a partner and be on the floor. Ricky was at the bar, I was front of the house. Four people. I love this word, hierarchy. I believe that hierarchy in the beginning set the course for the success we’ve had for 16 years. I still get teary-eyed when I think about it. I'm still together with my partners, even though I can be difficult at times.

Diarmit: Not at all. You’re a saint! [laughs] Next

Blackbird Chapters

- Log in or register to post comments